TBT

- Thread starter Meria

- Start date

SWAHILIS

The name Swahili is an Exonym derived from Arabic: سواحل, romanized: Sawāhil, lit. 'coasts'. Swahili people speak the Swahili language. Swahili people's endonym for themselves is Waungwana, which means "the civilized ones." Modern Standard Swahili, derived from the Kiunguja dialect of Zanzibar. Like many other world language, Swahili has borrowed a number of words from foreign languages, particularly administrative terms from Arabic, but also words from Portuguese, Hindi and German. Other, older dialects like Kimrima and Kitumbatu have far fewer Arabic loanwords, indicative of the language's fundamental Bantu nature. Kiswahili served as coastal East Africa's lingua franca and trade language from the ninth century onward. Zanzibari traders' intensive push into the African interior from the late eighteenth century induced the adoption of Swahili as a common language throughout much of East Africa. Thus, Kiswahili is the most spoken African language though it is used by far more than just the Waswahili themselves.

Today the Mombasa Swahilis are namely

*Wa jomvu

*Wa changamwe

*Wa Pate

*Wa Kilindini

*Wa Ngunya

*Wa Tangana

These are the remaining original Swahilis of Mombasa from 11th century before Shugwaya brought about the Taifas and the mijikenda

The name Swahili is an Exonym derived from Arabic: سواحل, romanized: Sawāhil, lit. 'coasts'. Swahili people speak the Swahili language. Swahili people's endonym for themselves is Waungwana, which means "the civilized ones." Modern Standard Swahili, derived from the Kiunguja dialect of Zanzibar. Like many other world language, Swahili has borrowed a number of words from foreign languages, particularly administrative terms from Arabic, but also words from Portuguese, Hindi and German. Other, older dialects like Kimrima and Kitumbatu have far fewer Arabic loanwords, indicative of the language's fundamental Bantu nature. Kiswahili served as coastal East Africa's lingua franca and trade language from the ninth century onward. Zanzibari traders' intensive push into the African interior from the late eighteenth century induced the adoption of Swahili as a common language throughout much of East Africa. Thus, Kiswahili is the most spoken African language though it is used by far more than just the Waswahili themselves.

Today the Mombasa Swahilis are namely

*Wa jomvu

*Wa changamwe

*Wa Pate

*Wa Kilindini

*Wa Ngunya

*Wa Tangana

These are the remaining original Swahilis of Mombasa from 11th century before Shugwaya brought about the Taifas and the mijikenda

Aviator

Elder Lister

There's a story about how Dedan Kimathi killed a mzungu in that motel.Why a Kiambu village is known as Zambezi

Nothing fascinates me than the PCEA Training Centre in Zambezi Kikuyu. Not that it is an extra-ordinary building but because of the past history. Of course few Kenyans know about this building – and its colonial bunkers- but at least those who have used the Nairobi-Nakuru Road know of Zambezi.

Now for many years this was the Zambezi Motel and it gave name to this village in the outskirts of Nairobi. Before it was re-opened on November 30, 1963 as the new Zambezi Motel, it had been lying desolate after it was abandoned by its previous owner.

That time, according to records, a 24-year Mrs Josephine Aron and her husband Sigi had decided to rehabilitate the building as the “best gesture of our faith in this lovely country”.

Josephine’s husband, was a land and real estate agent. Having worked in both Rhodesia and Zambia, he had fallen in love with the Zambezi River and wanted to immortalize his love by naming the 65-bedroom business, Zambezi Motel. It was actually the only motel, worth its name in Kenya. They also named their two cats, Zam and Bezi.

Designed to be a stop-over for motorists, it was expensively furnished, and had a site for caravans. A single would cost Sh 25 while a double was Sh45 by 1963. And by 1969 this had climbed to Sh45 for single ands Sh 80 for double. Zambezi was actually a luxurious stop over but before it was renovated it was simply Njogu-Inn. Owned by Mrs Berkley Mathews, Njogu-Inn was perhaps the best known hotel on the Nairobi-Nakuru Road. Her Husband E.J.H Mathew used to own the Kikuyu Estates – a huge swath of land which was later sold to James Gichuru, the pioneer minister for finance.

Mathews was one of the settlers who did not want to sample life under an African government and in 1963 shortly before independence she had offered it for sale for £32,000 – the entire building and its contents. But there were few takers for this. As more property was thrown into the market and with the fear of an African-led government reaching crescendo, the value plummeted to £6,000 and that is when it was purchased.

In one of her last interviews with a Kenyan paper, Mrs Mathews remarked: “We are sorry of course, but it is one of those things. We have already got rid of everything else…”

Njogu-Inn had been completed in 1953 just as the Mau Mau war broke. It was a bad investment; a bad bet. The owners had started constructing it in 1947 – the year that Jomo Kenyatta took over leadership of Kenya African union and started agitating for change. But few foreign investors thought that the “white man’s country” – as they called Kenya – would end up with an African government. Certainly not the Njogu-inn proprietor. But to safeguard her clients she build some bunkers underneath the building that were furnished too. Here, nobody would reach the clients – and even today, few at this church building know of these dark corners.

I recently came across an old review of Zambezi and the owner was grumbling that because it was far from the City, it was putting people off. Although she at one point dropped the cost of a double from Shs 80 to Sh 35. It failed to make economic sense. As the dollar crisis began in 1970s throwing the tourism industry into a spin. She sold it to PCEA Church as their training centre.

But the name she had abandoned Njogu-Inn for Zambezi had been picked a River Road trader who opened a hotel known as Njogu-Ini. It had the Njogu-Inn logo of an elephant although it means the place of elephants. How a place of worship was a beer hole is the untold story of Zambezi. Njogu-ini, the River Road bar, has survived ever since and Zambezi, the name, is now a village in Kikuyu. History continues…

Dig it up

on it.There's a story about how Dedan Kimathi killed a mzungu in that motel.

Dig it up

nissan datsun 1600cc

mzeiya

Elder Lister

But Saitoti died in 2012, not 2008Nigger tried so hard to shed off his true identity

Montecarlo

Elder Lister

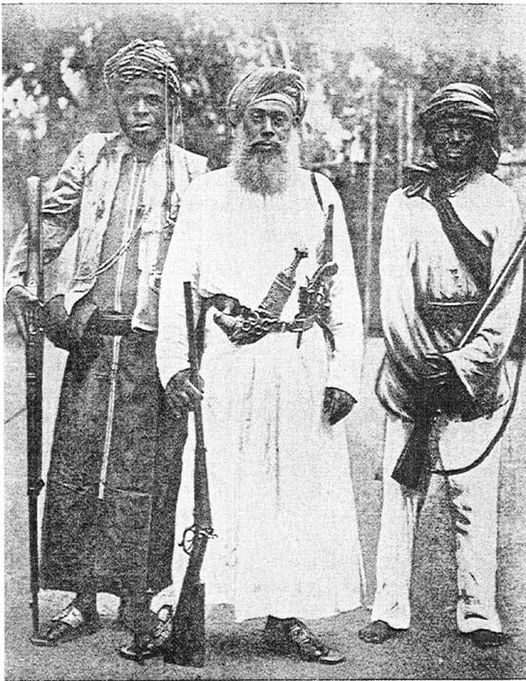

Does that story remind you of Jacob and Esau?SENTEU AND OLONANA

While Olonana (Lenana) is more known, Senteu ( also spelled Sendeu) was supposed to be Masai Oloiboni (Laibon) after the demise of their father, Mbatian. As the adage goes, when you play the Game Of Thrones, you win or you die.

Mbatian was on the point of death, when he called the elders of the Matapato, the locality where he resided and among other prophesies, told them that he wished his successor to be the son to whom he would give the Oloiboni insignia.

Senteu, Olonana’s elder brother from a different mother, is said to have requested their father Mbatian to bless him with leadership powers and was told to come the "following day" to go through the ritual that would have enabled him become the Oloiboni.

He was to be given the medicine man’s insignia but Olonana who was hiding nearby at the cow shed, overheard the discussion and pulled a first one on him, by rising up early to go and meet his ageing and frail father who was partially blind for the blessings.

Mbatian "unknowingly" blessed Olonana and gave him the medicine man’s insignia, the iron club, the medicine horn, the gourd, stones and his bag thinking he was Sendeu.

Sendeu later visited their father and after learning what had happened, became so furious and promised to do all he could to kill his young brother.

He was so determined to kill his brother after the succession and said: “I will not be subject to my brother. I will fight with him until I kill him” and when Olonana died, it was said Sendeu used his wife to kill him.

When the British arrived, Lenana welcomed them with open arms seeing a way of dealing with his brother once and for all.

But this division among other things ensured the Masai did not resist the intrusion of the white man, despite being the most powerful community back then.

In 1904, Lenana signed the Anglo-Masai treaty. The Masai were then evicted from their Naivasha grazing lands to the northern reserve of Laikipia and the southern one in Loita. The best lands in the Rift-valley now belonged to the Delameres and Co.

View attachment 53300

Fala12

Elder Lister

Inaitwa Irrigation Management Transfer. Happens all over ni venye hii ya mwea ilikuwa bloody juu government wasn't willingHISTORY OF THE SCHEME

Mwea Irrigation Scheme was started way back in 1956 and the predominant crop grown in the Scheme is rice. This is one of the seven public schemes under the management of the National Irrigation Board. It is situated in the newly created Kirinyaga South District, in the Kirinyaga County. The Scheme is about 100 Km North East of Nairobi.

Mwea Irrigation Scheme has a gazetted area of 30,350 acres. A total of 16,000 acres has been developed for paddy production. In addition to this, the scheme has a total of 4,000 acres of outgrower and jua kali areas under paddy production. The rest of the scheme is used for settlement, public utilities, subsistence and horticultural crops farming.

The scheme is served by two main rivers namely Nyamindi and Thiba rivers. Irrigation water is abstracted from the rivers by gravity by the help of fixed intake weirs, conveyed and distributed in the scheme via unlined open channels. There is a link canal joining the two rivers which transfers water from Nyamindi to Thiba River which serves about 80% of the scheme.

The scheme is developed on a gazetted land and the farmers were settled as tenants each with a holding of at least 4 acres. This acreage was based on the minimum economic acreage sufficient for the full time upkeep of the farmers. Due to the increase in the population, most of the holdings have been subdivided among family members and in other cases transferred to new farmers.

Since inception till 1998 the scheme was being run solely by the National Irrigation Board as mandated by the Irrigation Act Cap 347. The Board was responsible for all the activities in the production chain which includes land preparation, credit provision, crop husbandry activities, harvesting and post harvest handling including marketing. NIB used to undertake the milling and marketing of the crop through MRM from which they would recover their expenses after the sales. This system of farmers channeling their paddy through NIB collapsed during the 1998/99 crop when they revolted and refused to deliver the crop and instead demanded that they be allowed to market the crop on their own.

Following this sudden change of role of NIB in the scheme, the scheme management was briefly taken over by a Mwea Rice Farmer’s Cooperative Society (MRGM.) However, the farmers realized that they could not go it alone due to: lack of skilled personnel; Lack of finances and Lack of machinery for scheme maintenance. During this brief period when scheme was run by cooperative the infrastructure deteriorated and tail Enders could not crop.

In 2003, the farmers approached the government for assistance in the scheme management. NIB went through a restructuring process with a view of changing its mode of service delivery to the farmers in the schemes. Some of the non-core roles which used to be performed by NIB were devolved to the farmers and other

View attachment 53285

cc @Luther12 @Mwalimu-G @Fala12

fafanuailikuwa bloody

Montecarlo

Elder Lister

Wood Avenue is still referred to as wood Avenue...it's the road from Hurlingham total to Kawangware that was renamed Argwings Khodhek....his accident has always attracted some speculation...apparently he had a gunshot wound...not sure about this...Argwings Kodhek was born in 1923, shortly after Kenya became a British colony, in present day Siaya County, Gem constituency in Malanga, Gem location. He hailed from Kogolo-ojuodhi clan which is one of the most influential in the region. His baptismal name was Clement Michael George which was localized to ‘Chiedo Mor Gem’ which means ‘cooked/fried in Gem’. He attended a local missionary school and later joined St. Mary Yala for his Cambridge certificate before proceeding to St Mary Kisubi College and then Makerere. He returned to Kenya where he taught at Kapsabet boys which was then in Rift Valley province until 1947. While in Kapsabet, he met Daniel Moi who later became a member of legislative council, vice president and president of independent Kenya. Kodhek then became the first Kenyan to open a private law firm in 1957 at the height of Mau Mau resistance. He married a white woman, Mavis Tate, despite the prohibition of mixed-race marriages by colonial legislation, which he successfully battled in court. However, they could not live together in certain areas due to segregation laws which prohibited Africans from settling in the white neighbourhoods of Lavington, Karen and Muthaiga, hence they settled at Ruaraka. Later he divorced his Irish wife and married Joan Omondo, who died in 2013.

Yesterday marked 53 years since *Clementine Michael George Argwings kodhek (CMG)* The first Kenyan to become a barrister died in a Road Accident.

His car rolled several times at the Junction of Wood avenue and Ngong Road.

Wood Avenue would later change the name to Argwings kodhek Road in his honour.

Argwings kodhek represented Gem constituency before he died.

The second Kenyan barrister was *Jean Marie seroney* from Tinderet in modern day Nandi county.

View attachment 53249

Montecarlo

Elder Lister

Alot in this story is not true.HOW THE ‘CHAMELEON’ JOMO KENYATTA DID IT

Once came across a Newsnight archive feature on the 1980 Rhodesian (now Zimbabwe) elections, which showed the hopefulness of newly independent Africans — optimistic of the future and Robert Mugabe’s potential. Many white Rhodesians were, however, visibly angry and scared.

At the close of the report, the anchor offers consolation: “Remember Jomo Kenyatta, who was loathed and feared by Kenya’s whites as the Mau Mau leader and became the father of one of Africa’s most harmonious multiracial societies.”

Yet Kenyatta’s rule was plagued with corruption, political assassinations and violence committed against his own citizens. How did he become both a darling of the West and a hero of Afrocentric scholars?

Jomo Kenyatta’s life is a study in political astuteness, incredible luck and demagoguery. From the outset, young Kenyatta seemed to possess a wily political awareness. While working at an early age as a carpenter’s apprentice, store clerk and water meter reader, the future president changed his name from Johnstone Kamau to Johnstone Kenyatta.

The name also works as a play on the words Kenya and taa (light), meaning “light of Kenya” — no coincidence. When he later moved to London, he would assume “Jomo” in the place of Johnstone, reincarnating himself as Jomo Kenyatta, the African independence leader.

He realised how powerful-sounding Africanised names would be beneficial in his political career, decades ahead of African leaders like Zaire’s Mobutu (full name Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu waza Banga,) who would ride the wave of bombastic-sounding name changes in the late 1970s. His natural ability to manage his public image was key to the way he is remembered today.

After taking over the reins at the Kikuyu Central Association in 1927, Kenyatta would then travel to the United Kingdom, where he fell in with a communist crowd. After a short break studying in Russia, he moved back to London, gaining degrees at the University of Central London and the London School of Economics, where he published his celebrated (if nostalgic) thesis on the Agikuyu culture, Facing Mount Kenya.

Returning to Kenya in the early 1930s, he found a country where politics had moved forward, and the Kikuyu were even more agitated about land issues. A political chameleon, his communist association and experience as leader of the long-standing colonial agitator, the Kikuyu Central Association, would win him support of the radicals. At the same time, his social “finesse” and academic credentials could woo the constitutional (democrat) factions.

Advancing in age, he utilised African respect for the elders to place himself as the sole leader of the independence movement. This grew to the extent that when he was arrested by colonial authorities, “no uhuru (freedom) without Kenyatta” was the clarion call across the board.

Yet, it’s only after independence that the real Kenyatta emerges.

As leader of the Kenya African National Union, he won the 1963 election and took up the position of prime minister. Under his lead, Kenya moved from a colony to a republic.

The country’s first president must have learned something in his Western sojourn. He came back with a big appetite for land. His family, friends and other hangers-on engaged in rapacious grabbing of lands then owned by the departing British settlers. The practices of the former oppressors seemed to come easily.

Kenyatta also presided as the disappearances and deaths of politicians began to take place: first was Pio Gama Pinto and then, famously, Tom Mboya and JM Kariuki. This coincided with an increasing dissent within the ruling National Union Party.

He also abused traditional systems to ensure fealty.

With freedom won, Kenyatta’s government had to tackle the Mau Mau freedom fighters, who had fought the British and now came back to a life without jobs or land. For them the only tenable difference was that the overlords had changed; it was no longer the British lording over the country’s wealth, but the nouveau riche.

So, as the promise of land redistribution faded away, the president drew on the famed oathing of warriors. This tribe-wide oath (sometimes forced) saw people swearing to always support him as their leader.

Beyond Kenya’s Central Province, Kenyatta did not hesitate to use violence to quash any rumblings of discontent. Most notable was the five-year-long Shifta War against Kenyan Somalis that resulted in the deaths of tens of thousands.

Outside of the country’s borders, and as colonialism fell, Kenyatta sang the tune of “African solidarity” without ever rocking the boat on the international stage.

He was also one of the few African leaders to continue relations with apartheid South Africa. An early ally of Israel, unlike then-African governments, he even provided Kenyan airports and airspace for the 1970s Israeli raid on Entebbe in neighbouring Uganda.

Yet, there were no sanctions for Kenyatta, no gruesome Hollywood epics detailing the rollercoaster ride that took him from shamba-boy to a London socialite; rebellion in the forests to Benz-driving fatcat; to paranoid megalomaniac, ally to apartheid and finally ruthless oppressor.

Instead, he is remembered as a pan-Africanist leader. Why?

This requires much deeper research.

It may very well have to do with his constant shedding of his skin. Thanks to his knack of being able to read the signs and reinvent himself, he saved himself from the fate of numerous independence leaders who were killed or overthrown in later years, dying in office of a heart attack.

Kenya was, and remains, a vital ally and “anchor state” to the West; these foundations were laid by Kenyatta, and perhaps as a token of thanks, he has been spared the indignity of exposure by Western popular culture in a way that former Ugandan dictator Idi Amin was not.

View attachment 53318View attachment 53319

Jommo was not interested in leadership.....he never assumed the leadership of KCA. He was requested by James Beauttah to represent him because he (Jommo) could express himself well in English. Eventually Jommo joined KCA and became its Sec Gen.

Koinange would then consistently involve Kenyatta in political gatherings and the sole reason was Kenyatta's level of education and experience in UK.

On land appetite, it was Koinange who used to insist that an African leader cannot appear to be poor. He must have property ...this and the respect Jommo had for Mbiyu led to the laters avarice for land couple that with an equally avaricious wife and Jommo became mean and corrupt. Note all the children of paramount chiefs had a knack for land for they had grown up in large compounds and their fathers had large tracts of land. Jommo was very poor...he came from real poverty.

To cement their friendship Mbiyu suggested that Jommo disown his mzungu wife Edna Clarke and marry his sister who died giving birth...