Everyone agrees (despite claims to the contrary!) that the pandemic should sharply reduce activity. It's just not healthy to try to keep the economy going like before.

But once you move past this basic consensus there are disagreements.

Reasonable people debate: is this purely a supply shock or also a demand shock? This matters. It affects the macro policy response, monetary and fiscal.

Our perspective: demand is not exogenous and a negative supply shock can trigger too strong a response in demand.

Supply ---> Demand

To thinking about this relation deep we need to go beyond the most basic macro models. Sectoral heterogeneity is important. So are financial frictions, for households, as well as firms.

This is, most basic macro model gives you exact opposite: negative supply shock does not reduce demand enough! Representative agent single-sector model may recommend raising interest rates right now!

Fortunately, the policy discussions from all sides have been much wiser.

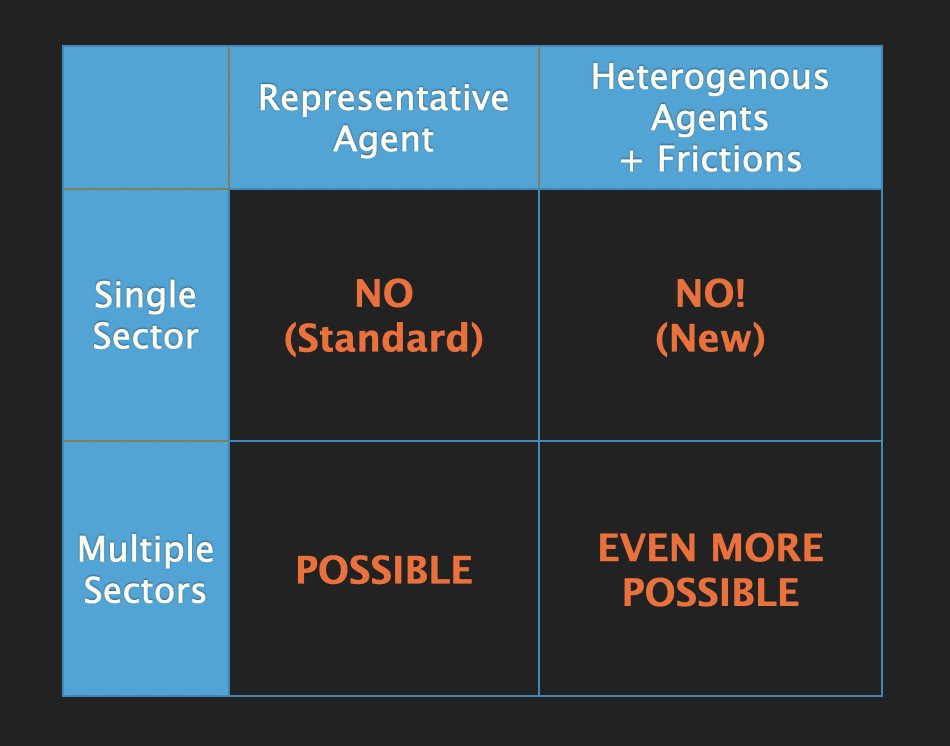

This chart summarizes some of our results. Moving towards more realism from left to right, from top to bottom.

This surprised us: financial frictions (cash-constrained consumers) isn't enough to get things going and get demand deficiency.

It is important to think of different sectors, the shock hits asymmetrically. it's not the same if we all lose 50%, than if half of us to lose 100%!

This is true even without credit frictions, but even more true with credit frictions (an interaction).

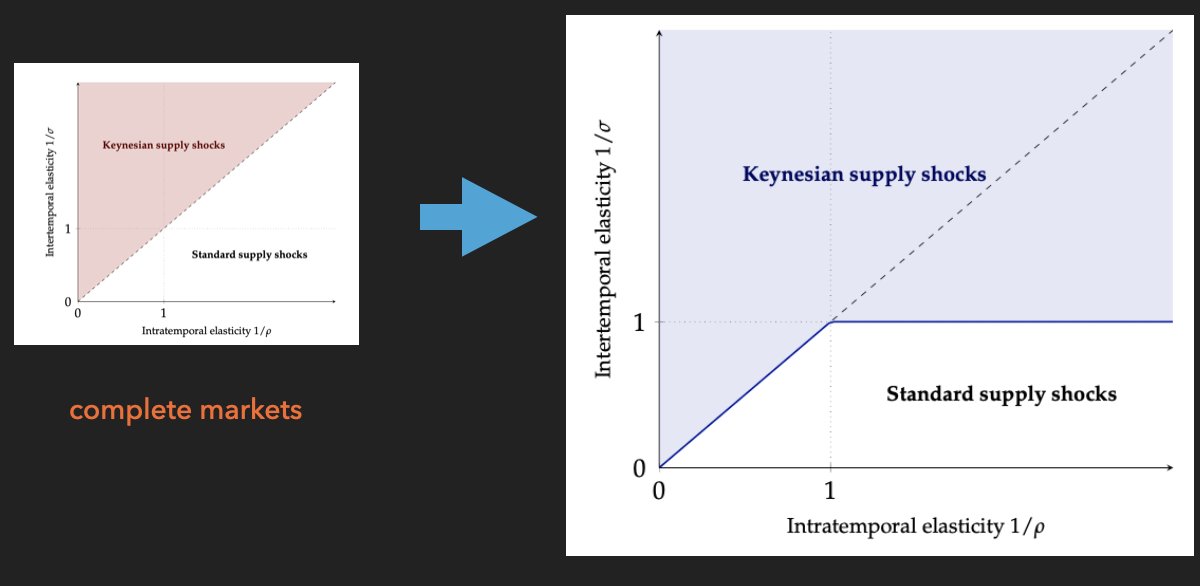

The parameter space where we you predict demand deficiency (we call it Keynesian Supply Shock) grows, when markets are incomplete:

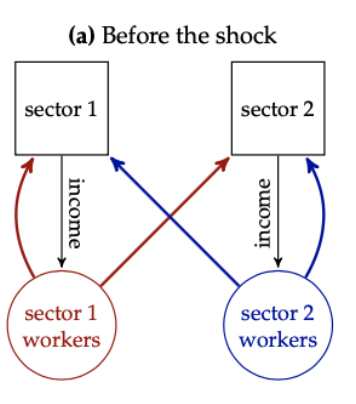

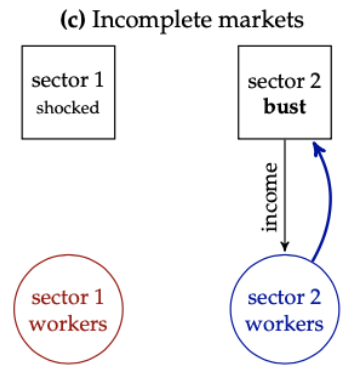

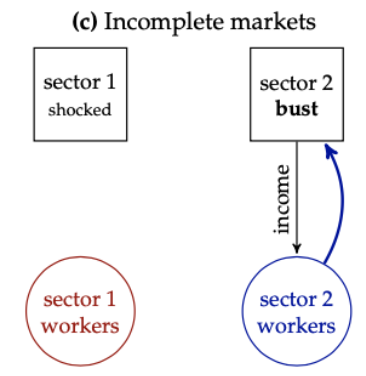

Here is the intuition. Start with the healthy economy. The chart shows two sectors. Different workers work in each, but consume from both.

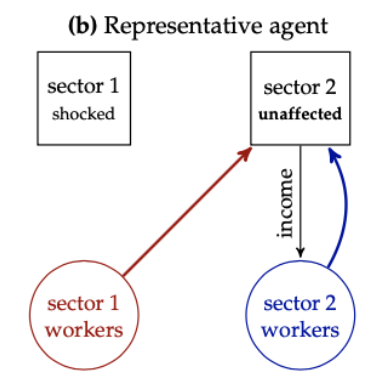

But now shut down sector 1. For the idilic representative agent this looks like this.

Although demand and work in sector 2 may fall, workers hit in sector 1 still buy stuff from 2, because they are perfectly insured.

But absent perfect insurance, workers from sector 1 will cut back further. Then things get bad in sector 2 and we have a further bust.

A result we weren't expecting...

Fiscal policy may lack potency, very little bang for the buck.

[stay with me, it will make a comeback]

Some argued this (I think!) based on idea that propensity to spend on the margin is low now.

This is certainly true. But we find another reason: the Keynesian "virtuous cycle" of my spending is my income, turns out to be short circuited.

This means the multiplier can be low not just because of low propensities to spend.

Remember this figure? Transferring cash to workers in 1 helps them and helps sector 2: they spend it on sector 2 and, being short on cash, have higher propensity to spend.

But there is no longer a feedback from this extra spending to their own income! The chain is cut.

Actually, this relates to work by Christina Patterson. She looks at correlation between the sensitivity of your income to total income and your marginal propensity to spend (MPC).

She finds a positive correlation, which makes multipliers bigger.

What we are arguing is that in these unusual times this can flip! People out of work in a shutdown sector have high MPC but may not benefit when non-shutdown sectors improve.

Now, this doesn't mean that fiscal policy and social insurance is not important! I'll get to that. It is hugely important.

Moving on, we also study business closings and labor hoarding.

Policy discussions have centered around the concern that businesses will also suffer. Lower sales. Might also be cash constrained.

We do two things.

I'll get to labor hoarding for shutdown sectors later. First, what might happen to businesses that are not shut down, but face lower demand? Restaurants close, but clothing and other shops suffer.

We find this can create a chain reaction, multiplying the initial effect.

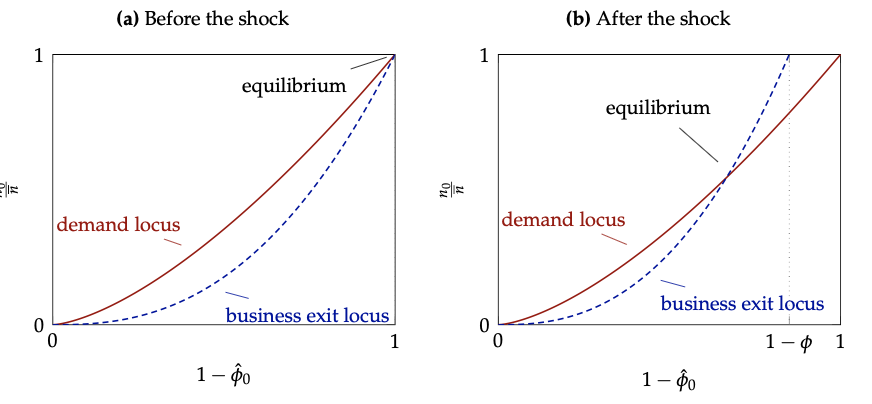

Won't explain this figure in detail, but horizontal axis represents open businesses.

On left, before shutdown everyone is open: blue and red meet at 1.

On right, we shut down a fraction of firms (dotted vertical line), this moves blue curve and closes even more businesses.

Probably most of the policy debate on businesses revolves around firms that are shutdown. How will they get back up when this is eventually over? Will firms keep job-worker matches? Meanwhile, might they keep and pay their workers (lobor hoarding) or lay them off?

We try to get at that in the paper, with a section on labor hoarding. We realized thinking about this that there isn't enough modeling about labor hoarding. We do something quite simple.

Firms trade off paying wage, versus losing surplus from match in future.

Our model says there is a double benefit from firms hoarding their workers and paying them.

First, paying them obviously supports workers in need (a kind of private insurance) which helps the macroeconomy.

Second, preserving matches improves productivity for the recovery.

In our model policy can help. First, this may give an extra motive for monetary easing. Lowering the rate helps firms be more forward-looking, weigh future surplus vs. paying wage today. Second, if firms are cash-constrained then providing liquidity can help.

research by Ivan Werning