yes.@Meria there's this road in Ngando, Dagoretti south inaitwa Wahu rd, is it after Grace Wahu!

huko uko home

unamkumbuka musubcuonty?

ata yeye is not far from there

yes.@Meria there's this road in Ngando, Dagoretti south inaitwa Wahu rd, is it after Grace Wahu!

The TRUTH! NOTHING BUT THE TRUTH.

Now people know how Jeff Koinange and Uhuru are relatedJomo Kenyatta's 3rd wife Grace Wanjiku Koinange, daughter to senior chief Koinange and sister to once powerful minister Mbiyu Koinange and Fred Koinange(Jeff Koinange's dad).. She died while giving birth to her only child, Jane Makena Gechaga.

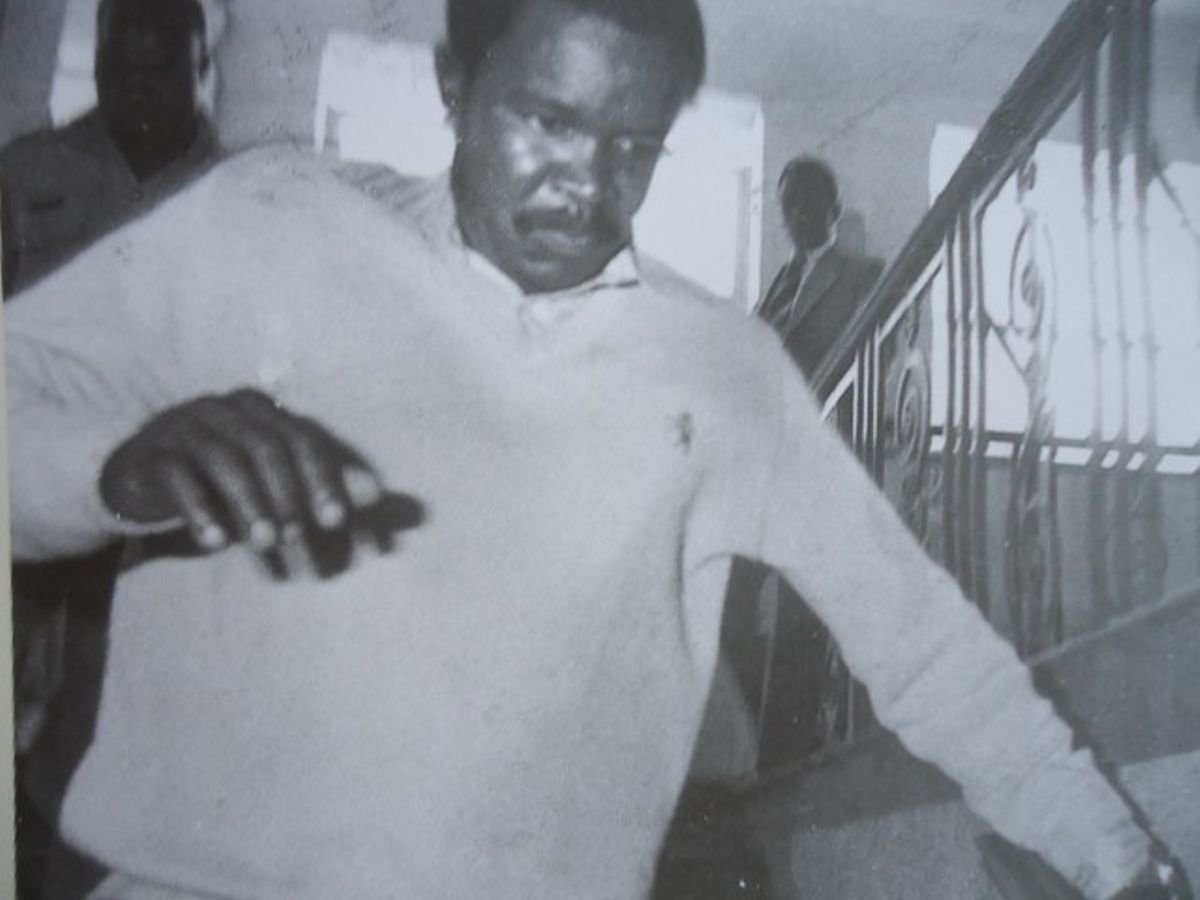

View attachment 14154View attachment 14155

Yes tumesikia

tell me about all luyia subtribesYes tumesikia

The true meaning of Wamunyota. Hadi maandamano ? It was rumored being warned by his doktari to give up the drink lest it kills him he asked the dok to remove any organ that does not agree with fobe. @Makanika murefi niaje.First Finance minister whose love for work and the bottle was unmatched

We have simply forgotten our first Finance minister James Samuel Gichuru. The 36th anniversary of his death, last month, was passed quietly — yet, as we start debate on our currency, here is the man who was at the helm when we got our own Central Bank.

Mr Gichuru, mwalimu to his peers, oversaw the demise of the East African Currency Board and the rise of a Central Bank to not only provide banking services for the commercial banks but become an instrument of official monetary policy.

KARA BAR

His success is often overshadowed by his love of beer — so much, so that when President Jomo Kenyatta was opening the first Central Bank, on September 14, 1966 at the former Army Pay and Records Office off Harambee Avenue, his Finance minister was not in sight. It was assumed, perhaps correctly, that he was either at home inebriated — or at his favourite drinking hole, Karai Bar on River Road.

NO TEA

Kenyatta and Gichuru were buddies and there are many accounts of his dalliance with tipple. Once at a morning meeting at State House, Nakuru, officials of the Defence ministry, who included Permanent Secretary Jeremiah Kiereini and Deputy Secretary Phillip Gitonga, had been welcomed by First Lady, Mama Ngina Kenyatta for breakfast.

Every asked for some tea and coffee apart from Mr Gichuru who asked for a beer. Mama Ngina, rather than pester the man from Kiambaa, gave him a drink, perhaps two. The wait was long for Mzee Kenyatta — and when he came, he asked Mr Gichuru why he was taking beer in the morning.

DISCIPLINARIAN

“What did you want me to drink and we have been waiting for you for so long,” recalls Gitonga in his biography.

“Can’t you take tea like the others,” Mzee questioned.

“Who me? Drink tea? No!” Gichuru exclaimed in Kikuyu. “I can’t take tea,” he added with some finality.

And that was unlike the Gichuru who was known in his heyday as a teacher at Alliance High School as a strict disciplinarian.

POLITICAL CANDLE

Kenyatta tolerated Mr Gichuru — for he is the one who extinguished his political candle, twice, to let Kenyatta’s shine.

When Kenyatta was in Europe, Mr Gichuru was elected the President of the Kenya African Union but upon Kenyatta’s return, he stepped down in 1949 to allow Jomo take over the leadership. Again, when the state of emergency was declared in 1952, Mr Gichuru kept the banner of nationalism flying until 1957 when constitutional politics resumed.

GEOPOLITICS

It was as Kenya’s Finance minister that Mr Gichuru earned accolades alongside his equivalents: Amos Sempa (Uganda) and Paul Bomani (Tanzania).

The demise of the East African shilling, which was the common currency for the three East African countries, had offered Mr Gichuru many challenges as minister.

At the political level, the governments of President Julius Nyerere in Tanzania, Kenya’s Jomo Kenyatta and Uganda’s Milton Obote had their own suspicions on forming an East African Federation which was still on the table. It was also caught up in the geo-politics. While this federation was supposed to provide a forum for evolving area-wide policies, it was soon sacrificed by politics although the common East African shilling currency continued without a Central Bank until 1965 when separate countries started their own.

MUCH RESPECTED

Mr Gichuru was at the centre of all this drama — and he openly wondered how a single Central Bank for three countries would work in terms of policy formulation. The East African Currency Board had also warned that the experiment with a single Central Bank had not been tried elsewhere in the world.

Capital flight was what was worrying Mr Gichuru — and why he is so much respected as a finance minister — is that he managed this post-independent crisis which was hurting its economy, even without a Central Bank.

CAPITAL FLIGHT

On June 11, 1965, he had taken the Exchange Control Bill to Parliament taking a cue from Kenneth Kaunda’s Zambia, which had done the same. While the Zambian nation had a Central Bank capable of managing the flight, Gichuru was facing the single dilemma of lacking a Central Bank.

At that time, much of the currency was leaving the country via Aden (now South Yemen) which was a member of the East Africa Currency Board and was also using the East African shilling as its official currency. That year, Aden had requested to leave the board and federate with other Arab states.

TECHNOCRATS

With the enactment of the 1965 Exchange Control Act, the outflow of the long-term capital which had been running at high levels was reversed and large inflow of long-term capital recorded. Had Gichuru not done that, the Kenyan economy would have taken an early beating.

Perhaps it was him — or that he was surrounded by good technocrats like John Michuki, Philip Ndegwa and Duncan Ndegwa.

BUDGET SPEECH

Michuki, according to Duncan Ndegwa always reported Mr Gichuru to Kenyatta. Actually, Duncan recalls the story of Central Bank vividly: “Four hours before the official opening of the Central Bank of Kenya (in 1966) by the President himself, Gichuru failed to wake up, forcing Dr (Njoroge) Mungai (then Minister for Defence) to rummage all over for Gichuru’s written speech … year after year, the Permanent Secretary John Michuki reported the minister’s failure to react on policy choices.”

The worst was yet to come and happened in Mr Gichuru’s final budget speech: “Halfway into completing the Budget speech in Parliament, Gichuru fumbled in front of the eyes of honourable members, diplomats … and the President.”

SURPRISED

That day, Mr Gichuru had been with his PS Michuki at the Treasury for much of the morning rehearsing the Budget presentations. According to Mr Ndegwa, then the Central Bank Governor, “a break was allowed for the minister to top up, maybe at Karai Bar,” on River Road and that is the state which the minister read his speech.

According to Mr Ndegwa, how Mr Gichuru managed to run the ministry always surprised them: “The greatest contribution he (Gichuru) ever made was to let civil servants run the ministry, because although he was in-charge of a very sensitive ministry and had good common sense, he lacked focus. His two permanent secretaries, John Butter and Michuki, more or less steered the Ministry of Finance without the minister.”

SENSITIVE PAPERS

Shortly after independence, Mr Gichuru had favoured the retention of Mr Butter as the PS and officials were forced to create a supernumerary position for Michuki at the ministry. Butter’s duty was to administer the loans from Britain and he for years chaired the Land Bank. With him and Michuki handling everything, Mr Gichuru, then in his early 40s, had been left to run amok and at one point left some sensitive government documents at the Karai Bar!

Interestingly, during his tenure, the average gross domestic product (GDP) averaged 6.5 per cent. He had also inherited some hefty loans contracted by the colonial government during the 1940s and 1950s all due to foreign banks in 1965 and for about Sh100 million.

POLICY MEASURES

Also, he had to reimburse the white settlers for the land they were vacating, and wean the country away from dependence on the British Treasury, which was supplying 24 percent of government revenues in 1962-63.

To manage this state of economic affairs, Gichuru had to turn to long-term borrowing on domestic capital markets after the imposition of exchange controls in 1965.

This had allowed Mr Gichuru to succeed remarkably well in the tasks confronting him as the first minister for finance. Some of the most outstanding policy measures that still inform the national economy were brought during Gichuru’s tenure — a reason that he needs to be celebrated.

ACCOLADE

Postscript: One day, the Limuru residents went to Kenyatta’s Gatundu home to complain about Mr Gichuru’s drinking. By coincidence, Mr Gichuru was there too. He was given a beer, according to Duncan Ndegwa. And he started speaking: “How can anybody say that I err by drinking? I work very hard, so I have to drink. Look, I have been given this beer here, thanks to your hospitality. Could I refuse? Do you think ministers are appointed to play football?”

For years at the Karai Bar before it was demolished, the portrait of James Gichuru adorned the wall alongside that of Mzee Kenyatta. An accolade to a former patron. Perhaps.

View attachment 14172

There was Eric Awori reverse driver record holder, he conned a whole countryYaani hakuna subua kwa hii family

Haiya ajeThere was Eric Awori reverse driver record holder, he conned a whole country

Haiya.Haiya aje

Ati conned Kenyans? Niga got the whole world enthralled.Haiya.

Yaani hujui about a kenyan who cheated the whole country kuna rally ya driving in reverse in Australia and for tizi he reversed a msedes from msa to nrb.

Alafu tukamchangia.

Google it then uweke hapa

Yuko related na yule Gichuru wa Kenya power & Lighting company?First Finance minister whose love for work and the bottle was unmatched

We have simply forgotten our first Finance minister James Samuel Gichuru. The 36th anniversary of his death, last month, was passed quietly — yet, as we start debate on our currency, here is the man who was at the helm when we got our own Central Bank.

Mr Gichuru, mwalimu to his peers, oversaw the demise of the East African Currency Board and the rise of a Central Bank to not only provide banking services for the commercial banks but become an instrument of official monetary policy.

KARA BAR

His success is often overshadowed by his love of beer — so much, so that when President Jomo Kenyatta was opening the first Central Bank, on September 14, 1966 at the former Army Pay and Records Office off Harambee Avenue, his Finance minister was not in sight. It was assumed, perhaps correctly, that he was either at home inebriated — or at his favourite drinking hole, Karai Bar on River Road.

NO TEA

Kenyatta and Gichuru were buddies and there are many accounts of his dalliance with tipple. Once at a morning meeting at State House, Nakuru, officials of the Defence ministry, who included Permanent Secretary Jeremiah Kiereini and Deputy Secretary Phillip Gitonga, had been welcomed by First Lady, Mama Ngina Kenyatta for breakfast.

Every asked for some tea and coffee apart from Mr Gichuru who asked for a beer. Mama Ngina, rather than pester the man from Kiambaa, gave him a drink, perhaps two. The wait was long for Mzee Kenyatta — and when he came, he asked Mr Gichuru why he was taking beer in the morning.

DISCIPLINARIAN

“What did you want me to drink and we have been waiting for you for so long,” recalls Gitonga in his biography.

“Can’t you take tea like the others,” Mzee questioned.

“Who me? Drink tea? No!” Gichuru exclaimed in Kikuyu. “I can’t take tea,” he added with some finality.

And that was unlike the Gichuru who was known in his heyday as a teacher at Alliance High School as a strict disciplinarian.

POLITICAL CANDLE

Kenyatta tolerated Mr Gichuru — for he is the one who extinguished his political candle, twice, to let Kenyatta’s shine.

When Kenyatta was in Europe, Mr Gichuru was elected the President of the Kenya African Union but upon Kenyatta’s return, he stepped down in 1949 to allow Jomo take over the leadership. Again, when the state of emergency was declared in 1952, Mr Gichuru kept the banner of nationalism flying until 1957 when constitutional politics resumed.

GEOPOLITICS

It was as Kenya’s Finance minister that Mr Gichuru earned accolades alongside his equivalents: Amos Sempa (Uganda) and Paul Bomani (Tanzania).

The demise of the East African shilling, which was the common currency for the three East African countries, had offered Mr Gichuru many challenges as minister.

At the political level, the governments of President Julius Nyerere in Tanzania, Kenya’s Jomo Kenyatta and Uganda’s Milton Obote had their own suspicions on forming an East African Federation which was still on the table. It was also caught up in the geo-politics. While this federation was supposed to provide a forum for evolving area-wide policies, it was soon sacrificed by politics although the common East African shilling currency continued without a Central Bank until 1965 when separate countries started their own.

MUCH RESPECTED

Mr Gichuru was at the centre of all this drama — and he openly wondered how a single Central Bank for three countries would work in terms of policy formulation. The East African Currency Board had also warned that the experiment with a single Central Bank had not been tried elsewhere in the world.

Capital flight was what was worrying Mr Gichuru — and why he is so much respected as a finance minister — is that he managed this post-independent crisis which was hurting its economy, even without a Central Bank.

CAPITAL FLIGHT

On June 11, 1965, he had taken the Exchange Control Bill to Parliament taking a cue from Kenneth Kaunda’s Zambia, which had done the same. While the Zambian nation had a Central Bank capable of managing the flight, Gichuru was facing the single dilemma of lacking a Central Bank.

At that time, much of the currency was leaving the country via Aden (now South Yemen) which was a member of the East Africa Currency Board and was also using the East African shilling as its official currency. That year, Aden had requested to leave the board and federate with other Arab states.

TECHNOCRATS

With the enactment of the 1965 Exchange Control Act, the outflow of the long-term capital which had been running at high levels was reversed and large inflow of long-term capital recorded. Had Gichuru not done that, the Kenyan economy would have taken an early beating.

Perhaps it was him — or that he was surrounded by good technocrats like John Michuki, Philip Ndegwa and Duncan Ndegwa.

BUDGET SPEECH

Michuki, according to Duncan Ndegwa always reported Mr Gichuru to Kenyatta. Actually, Duncan recalls the story of Central Bank vividly: “Four hours before the official opening of the Central Bank of Kenya (in 1966) by the President himself, Gichuru failed to wake up, forcing Dr (Njoroge) Mungai (then Minister for Defence) to rummage all over for Gichuru’s written speech … year after year, the Permanent Secretary John Michuki reported the minister’s failure to react on policy choices.”

The worst was yet to come and happened in Mr Gichuru’s final budget speech: “Halfway into completing the Budget speech in Parliament, Gichuru fumbled in front of the eyes of honourable members, diplomats … and the President.”

SURPRISED

That day, Mr Gichuru had been with his PS Michuki at the Treasury for much of the morning rehearsing the Budget presentations. According to Mr Ndegwa, then the Central Bank Governor, “a break was allowed for the minister to top up, maybe at Karai Bar,” on River Road and that is the state which the minister read his speech.

According to Mr Ndegwa, how Mr Gichuru managed to run the ministry always surprised them: “The greatest contribution he (Gichuru) ever made was to let civil servants run the ministry, because although he was in-charge of a very sensitive ministry and had good common sense, he lacked focus. His two permanent secretaries, John Butter and Michuki, more or less steered the Ministry of Finance without the minister.”

SENSITIVE PAPERS

Shortly after independence, Mr Gichuru had favoured the retention of Mr Butter as the PS and officials were forced to create a supernumerary position for Michuki at the ministry. Butter’s duty was to administer the loans from Britain and he for years chaired the Land Bank. With him and Michuki handling everything, Mr Gichuru, then in his early 40s, had been left to run amok and at one point left some sensitive government documents at the Karai Bar!

Interestingly, during his tenure, the average gross domestic product (GDP) averaged 6.5 per cent. He had also inherited some hefty loans contracted by the colonial government during the 1940s and 1950s all due to foreign banks in 1965 and for about Sh100 million.

POLICY MEASURES

Also, he had to reimburse the white settlers for the land they were vacating, and wean the country away from dependence on the British Treasury, which was supplying 24 percent of government revenues in 1962-63.

To manage this state of economic affairs, Gichuru had to turn to long-term borrowing on domestic capital markets after the imposition of exchange controls in 1965.

This had allowed Mr Gichuru to succeed remarkably well in the tasks confronting him as the first minister for finance. Some of the most outstanding policy measures that still inform the national economy were brought during Gichuru’s tenure — a reason that he needs to be celebrated.

ACCOLADE

Postscript: One day, the Limuru residents went to Kenyatta’s Gatundu home to complain about Mr Gichuru’s drinking. By coincidence, Mr Gichuru was there too. He was given a beer, according to Duncan Ndegwa. And he started speaking: “How can anybody say that I err by drinking? I work very hard, so I have to drink. Look, I have been given this beer here, thanks to your hospitality. Could I refuse? Do you think ministers are appointed to play football?”

For years at the Karai Bar before it was demolished, the portrait of James Gichuru adorned the wall alongside that of Mzee Kenyatta. An accolade to a former patron. Perhaps.

View attachment 14172

noYuko related na yule Gichuru wa Kenya power & Lighting company?

I was already preparing my Arsenal against the "dynasties" but your answer is disappointing.

See the problems the MGTOW lifestyle plagued upon Kenya!Johnstone Kamau's first wife Grace Wahu, mother to Peter Muigai (former juja MP) and Margaret Kenyatta (former Nairobi mayor).

View attachment 14151View attachment 14152