TBT New Yr 2022 edition

- Thread starter Meria

- Start date

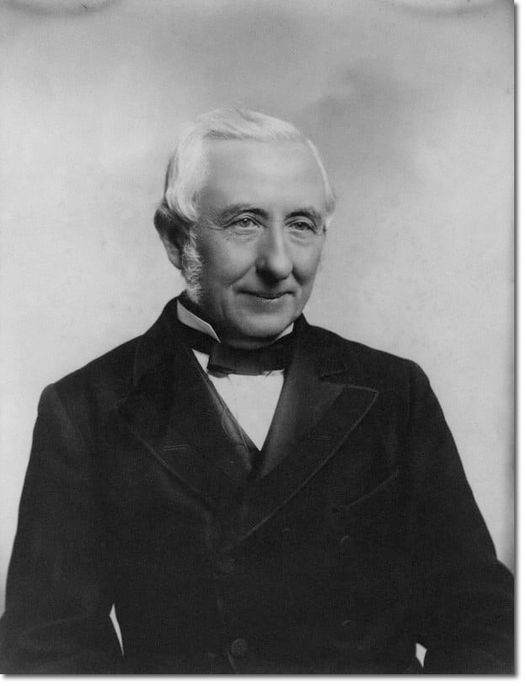

**THE FORGOTTEN MAN** - **Sir William Mackinnon, 1st Baronet CIE FRSGS** (13 March 1823 – 22 June 1893) He pioneered shipping and banking between India and East Africa. He was also first to establish churches in East Africa.

Sir Mackinnon was a Scottish ship-owner and businessman who built up substantial commercial interests in India and East Africa. He established the British-India Steam Navigation Company and the Imperial British East Africa Company.

Biography

Early life

He was born in Campbeltown, Argyll, and after starting in the grocery trade there, went to Glasgow and worked for a merchant who had Asian trading interests.

Career

Mackinnon went to India in 1847 and joined an old schoolfriend, Robert Mackenzie, in the coasting trade, carrying merchandise from port to port around the Bay of Bengal. Together they formed the firm of Mackinnon Mackenzie & Co and Mackinnon chose to make Cossipore the base for his own activities.

In 1856 he founded the shipping company Calcutta and Burma Steam Navigation Company, which would become British India Steam Navigation Company in 1862. It grew into a huge business trading round the coasts of the Indian Ocean, extending its operations to Burma, the Persian Gulf and the east coast of Africa, from Aden to Zanzibar.

In 1865 he established Gray, Dawes and Company as a merchant partnership for his nephew Archibald Gray and Edwyn Sandys Dawes (1838–1903), knighted in 1894. The company, founded as a shipping and insurance agency in the City of London, went through several reorganizations and ownership changes, obtaining recognition as a merchant bank in 1915, becoming fully fledged as Gray Dawes Bank in 1973 (sold in 1983), and now known as Gray Dawes Group Ltd

In 1888, Mackinnon founded the Imperial British East Africa Company and became its Chairman. The company, supported by the United Kingdom government as a means of establishing British influence in the region, was committed to eliminating the slave trade, prohibiting trade monopoly, and equal treatment for all nations. The company would later be taken over by the British government and became the East Africa Protectorate.

In 1889 Mackinnon was made 1st Baronet of Strathaird and Loup.

Mackinnon promoted Henry Morton Stanley's Emin Pasha Relief Expedition, first enlisting Stanley, then writing to government ministers including Lord Iddesleigh, the Foreign Secretary, and enlisting friends to form a committee which could oversee the expedition and meet more than half the cost. In 1891 he founded the Free Church of Scotland East African Scottish Mission

Sir Mackinnon was a Scottish ship-owner and businessman who built up substantial commercial interests in India and East Africa. He established the British-India Steam Navigation Company and the Imperial British East Africa Company.

Biography

Early life

He was born in Campbeltown, Argyll, and after starting in the grocery trade there, went to Glasgow and worked for a merchant who had Asian trading interests.

Career

Mackinnon went to India in 1847 and joined an old schoolfriend, Robert Mackenzie, in the coasting trade, carrying merchandise from port to port around the Bay of Bengal. Together they formed the firm of Mackinnon Mackenzie & Co and Mackinnon chose to make Cossipore the base for his own activities.

In 1856 he founded the shipping company Calcutta and Burma Steam Navigation Company, which would become British India Steam Navigation Company in 1862. It grew into a huge business trading round the coasts of the Indian Ocean, extending its operations to Burma, the Persian Gulf and the east coast of Africa, from Aden to Zanzibar.

In 1865 he established Gray, Dawes and Company as a merchant partnership for his nephew Archibald Gray and Edwyn Sandys Dawes (1838–1903), knighted in 1894. The company, founded as a shipping and insurance agency in the City of London, went through several reorganizations and ownership changes, obtaining recognition as a merchant bank in 1915, becoming fully fledged as Gray Dawes Bank in 1973 (sold in 1983), and now known as Gray Dawes Group Ltd

In 1888, Mackinnon founded the Imperial British East Africa Company and became its Chairman. The company, supported by the United Kingdom government as a means of establishing British influence in the region, was committed to eliminating the slave trade, prohibiting trade monopoly, and equal treatment for all nations. The company would later be taken over by the British government and became the East Africa Protectorate.

In 1889 Mackinnon was made 1st Baronet of Strathaird and Loup.

Mackinnon promoted Henry Morton Stanley's Emin Pasha Relief Expedition, first enlisting Stanley, then writing to government ministers including Lord Iddesleigh, the Foreign Secretary, and enlisting friends to form a committee which could oversee the expedition and meet more than half the cost. In 1891 he founded the Free Church of Scotland East African Scottish Mission

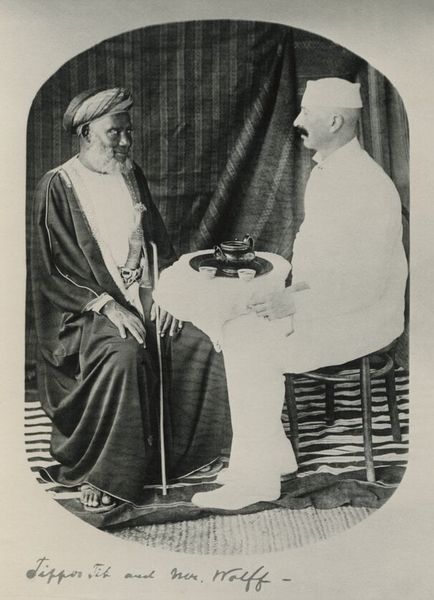

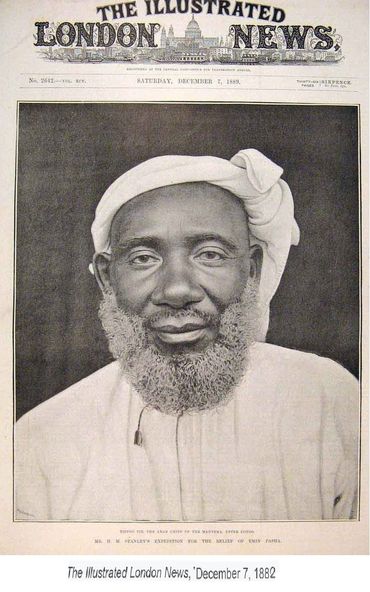

**Tippu Tip (1832 –1905**), was an Afro-Omani ivory and slave trader, explorer, governor and plantation owner. He worked for a succession of the sultans of Zanzibar. Tippu Tip traded in slaves for Zanzibar's clove plantations. As part of the large and lucrative ivory trade, he led many trading expeditions into Central Africa, constructing profitable trading posts deep into the region. He bought the ivory from local suppliers and resold it for a profit at coastal ports. He was also the most well known slave trader in Africa, supplying much of the world with black slaves.

Based on descriptions of his age at different points in his life, it is believed that Tippu Tip was born around 1832 in Zanzibar. Tippu Tip's mother, Bint Habib bin Bushir, was a Muscat Arab of the ruling class. His father and paternal grandfather were coastal Arabs of the Swahili Coast who had taken part in the earliest trading expeditions to the interior. His paternal great-grandmother, wife of Rajab bin Mohammed bin Said el Murgebi, was the daughter of Juma bin Mohammed el Nebhani, a member of a respected Muscat (Oman) family, and a Bantu woman from the village of Mbwa Maji, a small village south of what would later become the German capital of Dar es Salaam.

Throughout his lifetime Hamad bin Muhammad bin Juma bin Rajab el Murjebi was more commonly known as Tippu Tib, which translates to "the gatherer together of wealth".[1] According to him, he was given the nickname Tippu Tip after the "tiptip" sound that his guns gave off during expeditions in Chungu territory.

At a relatively young age, Tippu Tip led a group of about 100 men into Central Africa seeking slaves and ivory. After plundering several large swathes of land, he returned to Zanzibar to consolidate his resources and recruit for his forces. Following this he returned to mainland Africa.[4]

Later life[

Tippu Tip built a trading empire, using the proceeds to establish clove plantations on Zanzibar. Abdul Sheriff reported that when he left for his twelve years of "empire building" on the mainland, he had no plantations of his own. By 1895, he had acquired "seven 'shambas' [plantations] and 10,000 slaves"..

He met and helped several famous western explorers of the African continent, including David Livingstone and Henry Morton Stanley Between 1884 and 1887 he claimed the Eastern Congo for himself and for the Sultan of Zanzibar, Bargash bin Said el Busaidi. In spite of his position as protector of Zanzibar's interests in Congo, he managed to maintain good relations with the Europeans. When, in August 1886, fighting broke out between the Swahili and the representatives of King Leopold II of Belgium at Stanley Falls, al-Murjabī went to the Belgian consul at Zanzibar to assure him of his "good intentions". Although he was still a force in Central African politics, he could see by 1886 that power in the region was shifting.

Governor of the Stanley Falls District

In early 1887, Stanley arrived in Zanzibar and proposed that Tippu Tip be made governor of the Stanley Falls District in the Congo Free State. Both Leopold and Sultan Barghash bin Said of Zanzibar agreed and on February 24, 1887, Tippu Tip accepted.[7] At the same time, he agreed to man the expedition which Stanley had been commissioned to organize for the purpose of rescuing Emin Pasha (E. Schnitzer), the German governor of Equatoria (a region of Ottoman Egypt, today in South Sudan) who had been stranded in the Bahr el Ghazal area as a result of the Mahdi uprising in Sudan.[

Tippu Tip travelled back to the Upper Congo in the company of Stanley, but this time by way of the Atlantic coast and up the Congo River. Aside from its doubtful usefulness, the relief expedition was marred by the near annihilation of its rearguard, a disaster for which Stanley attempted to place the blame on Tippu Tip.

Congo–Arab War

After his tenure as governor, the Congo–Arab War broke out. Both sides fought with armies consisting mostly of local African soldiers fighting under the command of either Arab or European leaders.

When Tippu Tip left the Congo, the authority of King Leopold's Free State was still very weak in the Eastern parts of the territory and the power lay largely with local Arabic or Swahili strongmen. Amongst these were Tippu Tip's son Sefu bin Hamid and a trader known as Rumaliza in the area close to Lake Tanganyika.

In 1892, Sefu bin Hamed attacked Belgian ivory traders, who were seen as a threat to the Arab-Swahili trade. The Free State government sent a force under commander Francis Dhanis to the East. Dhanis had an early success when the African warlord Ngongo Lutete changed sides from Sefu's to his. The better armed and organised Belgian force defeated their opponents in several fights until the death of Sefu on 20 October 1893, and finally forcing also Rumaliza to flee to German territory in 1895.

After returning to Zanzibar around 1890/91, Tippu Tip retired. He set out to write an account of his life, which is the first example of the literary genre of autobiography in the Bantu Swahili language. Dr. Heinrich Brode, who knew him in Zanzibar, transcribed the manuscript into Roman script and translated it into German. It was subsequently translated into English and published in Britain in 1907.

Tippu Tip died June 13, 1905, of malaria (according to Brode) in his home in Stone Town, the main town on the island of Zanzibar.

Based on descriptions of his age at different points in his life, it is believed that Tippu Tip was born around 1832 in Zanzibar. Tippu Tip's mother, Bint Habib bin Bushir, was a Muscat Arab of the ruling class. His father and paternal grandfather were coastal Arabs of the Swahili Coast who had taken part in the earliest trading expeditions to the interior. His paternal great-grandmother, wife of Rajab bin Mohammed bin Said el Murgebi, was the daughter of Juma bin Mohammed el Nebhani, a member of a respected Muscat (Oman) family, and a Bantu woman from the village of Mbwa Maji, a small village south of what would later become the German capital of Dar es Salaam.

Throughout his lifetime Hamad bin Muhammad bin Juma bin Rajab el Murjebi was more commonly known as Tippu Tib, which translates to "the gatherer together of wealth".[1] According to him, he was given the nickname Tippu Tip after the "tiptip" sound that his guns gave off during expeditions in Chungu territory.

At a relatively young age, Tippu Tip led a group of about 100 men into Central Africa seeking slaves and ivory. After plundering several large swathes of land, he returned to Zanzibar to consolidate his resources and recruit for his forces. Following this he returned to mainland Africa.[4]

Later life[

Tippu Tip built a trading empire, using the proceeds to establish clove plantations on Zanzibar. Abdul Sheriff reported that when he left for his twelve years of "empire building" on the mainland, he had no plantations of his own. By 1895, he had acquired "seven 'shambas' [plantations] and 10,000 slaves"..

He met and helped several famous western explorers of the African continent, including David Livingstone and Henry Morton Stanley Between 1884 and 1887 he claimed the Eastern Congo for himself and for the Sultan of Zanzibar, Bargash bin Said el Busaidi. In spite of his position as protector of Zanzibar's interests in Congo, he managed to maintain good relations with the Europeans. When, in August 1886, fighting broke out between the Swahili and the representatives of King Leopold II of Belgium at Stanley Falls, al-Murjabī went to the Belgian consul at Zanzibar to assure him of his "good intentions". Although he was still a force in Central African politics, he could see by 1886 that power in the region was shifting.

Governor of the Stanley Falls District

In early 1887, Stanley arrived in Zanzibar and proposed that Tippu Tip be made governor of the Stanley Falls District in the Congo Free State. Both Leopold and Sultan Barghash bin Said of Zanzibar agreed and on February 24, 1887, Tippu Tip accepted.[7] At the same time, he agreed to man the expedition which Stanley had been commissioned to organize for the purpose of rescuing Emin Pasha (E. Schnitzer), the German governor of Equatoria (a region of Ottoman Egypt, today in South Sudan) who had been stranded in the Bahr el Ghazal area as a result of the Mahdi uprising in Sudan.[

Tippu Tip travelled back to the Upper Congo in the company of Stanley, but this time by way of the Atlantic coast and up the Congo River. Aside from its doubtful usefulness, the relief expedition was marred by the near annihilation of its rearguard, a disaster for which Stanley attempted to place the blame on Tippu Tip.

Congo–Arab War

After his tenure as governor, the Congo–Arab War broke out. Both sides fought with armies consisting mostly of local African soldiers fighting under the command of either Arab or European leaders.

When Tippu Tip left the Congo, the authority of King Leopold's Free State was still very weak in the Eastern parts of the territory and the power lay largely with local Arabic or Swahili strongmen. Amongst these were Tippu Tip's son Sefu bin Hamid and a trader known as Rumaliza in the area close to Lake Tanganyika.

In 1892, Sefu bin Hamed attacked Belgian ivory traders, who were seen as a threat to the Arab-Swahili trade. The Free State government sent a force under commander Francis Dhanis to the East. Dhanis had an early success when the African warlord Ngongo Lutete changed sides from Sefu's to his. The better armed and organised Belgian force defeated their opponents in several fights until the death of Sefu on 20 October 1893, and finally forcing also Rumaliza to flee to German territory in 1895.

After returning to Zanzibar around 1890/91, Tippu Tip retired. He set out to write an account of his life, which is the first example of the literary genre of autobiography in the Bantu Swahili language. Dr. Heinrich Brode, who knew him in Zanzibar, transcribed the manuscript into Roman script and translated it into German. It was subsequently translated into English and published in Britain in 1907.

Tippu Tip died June 13, 1905, of malaria (according to Brode) in his home in Stone Town, the main town on the island of Zanzibar.

THOMSON FALLS HOTEL 1985

@QuadroK4000 when are we demonstrating hii falls ibadilishwe jina, who the ferk was thompson???

@QuadroK4000 when are we demonstrating hii falls ibadilishwe jina, who the ferk was thompson???

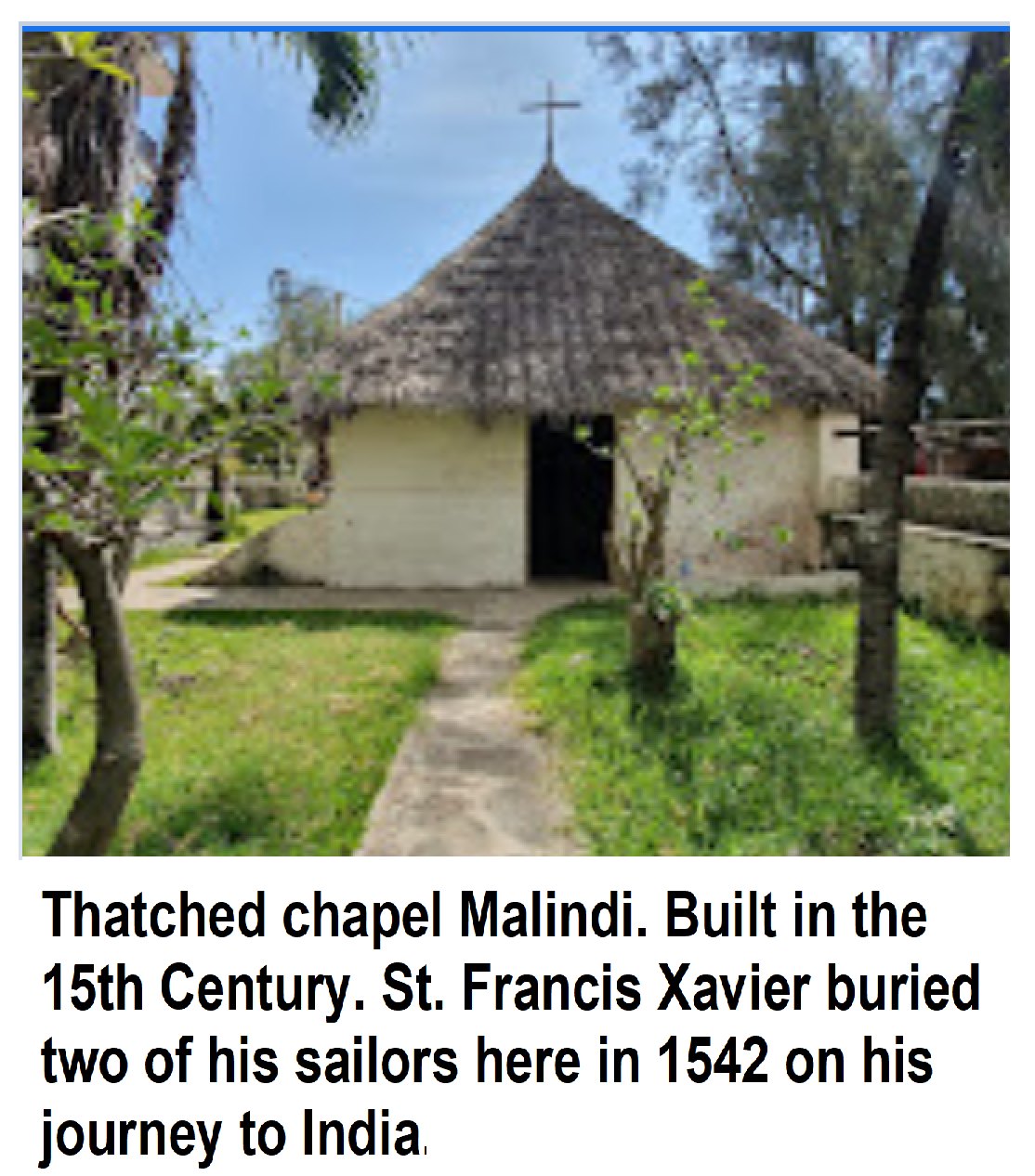

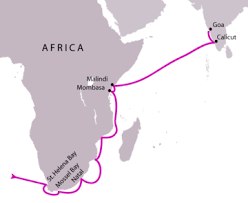

St. Francis Xavier 1506-1552

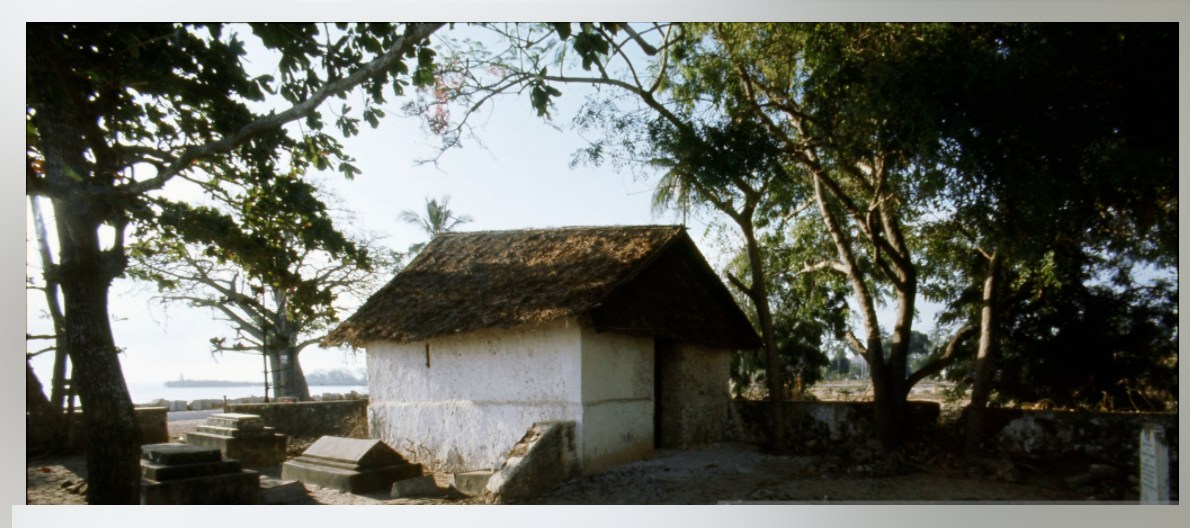

Portuguese presence in Malindi began with the arrival of Vasco de Gama in 1498. It is known that the chapel was built at the end of the 15th century. It is rather surprising that the authorities of an ancient Islamic city authorized the construction of a Christian church.

At that time the Portuguese travelling by sea were establishing trade bases everywhere on the East African coast. They were generally considered not to be welcome intruders because of their rapacity and harsh behavior. However, it seemed convenient to the Sultan of Malindi and the Portuguese to ally themselves with the Sultan of Mombasa and others.

Friendly relations were established which lasted throughout the 16th century. Thus, permission was granted to create a factory including warehouses, houses, offices and even a chapel.

The "enclave" lasted until the garrison retreated to Mombasa in 1593; after that date, the relations remained cordial for about a century. At that time, the "enclave" must have hosted about sixty Christians. For such a community the chapel and cemetery seem to be modest in size, but this was probably the decision. When the chapel was built, Islamic worship had reached a level of utmost importance: seventeen mosques, a sign of the greatness of this beautiful city.

In 1542 the famous missionary St. Francis Xavier, on his way to Goa, a Portuguese possession located on the west coast of the Indian peninsula, landed in Malindi to bury a sailor. In Rome Francis Xavier had founded the company of Jesus in 1534. Hence the interest and generosity of the company for the restoration of the chapel. The dedication to St. Francis has always been associated with the chapel. At the same time an important Muslim citizen told St. Francis that Islamic worship had waned and that only three mosques were still in use.

After the departure of the Portuguese, in 1593, the history of the chapel became obscure. During the 17th and 18th centuries the importance of Malindi declined and almost disappeared. During this period, it was described as ruined and abandoned. There are doubts that the chapel itself may have been reduced to ruin in various periods.

For about 300 years no historical information about it has been found.

The cemetery was used again when the first British District Commissioner of Malindi, J. Bell Smith, was buried there in 1894 and since then British governors and settlers have used it for a Christian burial. Other gravestones of the dead can be seen in the cemetery today, one of which bears the name of Charles Arnold Frank Mathews, the son of Canon Mathews, a pioneer of tea growing in Kenya, who went to Malindi on holiday in 1868 and drowned while swimming in the Indian Ocean.

Today the sepulchers of that time can still be seen, in the shade of tropical plants and the old church has been restored and only the memory and the place remains of the original one.

Portuguese presence in Malindi began with the arrival of Vasco de Gama in 1498. It is known that the chapel was built at the end of the 15th century. It is rather surprising that the authorities of an ancient Islamic city authorized the construction of a Christian church.

At that time the Portuguese travelling by sea were establishing trade bases everywhere on the East African coast. They were generally considered not to be welcome intruders because of their rapacity and harsh behavior. However, it seemed convenient to the Sultan of Malindi and the Portuguese to ally themselves with the Sultan of Mombasa and others.

Friendly relations were established which lasted throughout the 16th century. Thus, permission was granted to create a factory including warehouses, houses, offices and even a chapel.

The "enclave" lasted until the garrison retreated to Mombasa in 1593; after that date, the relations remained cordial for about a century. At that time, the "enclave" must have hosted about sixty Christians. For such a community the chapel and cemetery seem to be modest in size, but this was probably the decision. When the chapel was built, Islamic worship had reached a level of utmost importance: seventeen mosques, a sign of the greatness of this beautiful city.

In 1542 the famous missionary St. Francis Xavier, on his way to Goa, a Portuguese possession located on the west coast of the Indian peninsula, landed in Malindi to bury a sailor. In Rome Francis Xavier had founded the company of Jesus in 1534. Hence the interest and generosity of the company for the restoration of the chapel. The dedication to St. Francis has always been associated with the chapel. At the same time an important Muslim citizen told St. Francis that Islamic worship had waned and that only three mosques were still in use.

After the departure of the Portuguese, in 1593, the history of the chapel became obscure. During the 17th and 18th centuries the importance of Malindi declined and almost disappeared. During this period, it was described as ruined and abandoned. There are doubts that the chapel itself may have been reduced to ruin in various periods.

For about 300 years no historical information about it has been found.

The cemetery was used again when the first British District Commissioner of Malindi, J. Bell Smith, was buried there in 1894 and since then British governors and settlers have used it for a Christian burial. Other gravestones of the dead can be seen in the cemetery today, one of which bears the name of Charles Arnold Frank Mathews, the son of Canon Mathews, a pioneer of tea growing in Kenya, who went to Malindi on holiday in 1868 and drowned while swimming in the Indian Ocean.

Today the sepulchers of that time can still be seen, in the shade of tropical plants and the old church has been restored and only the memory and the place remains of the original one.

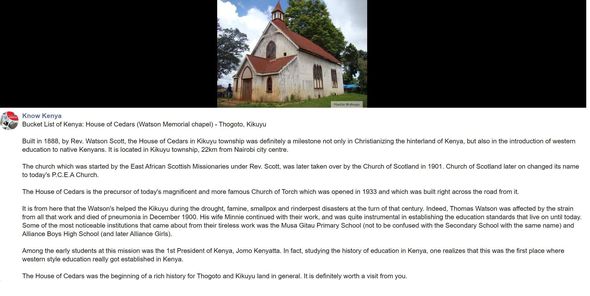

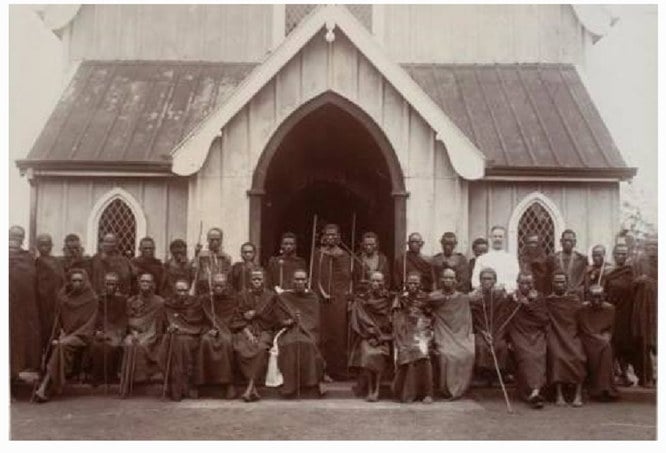

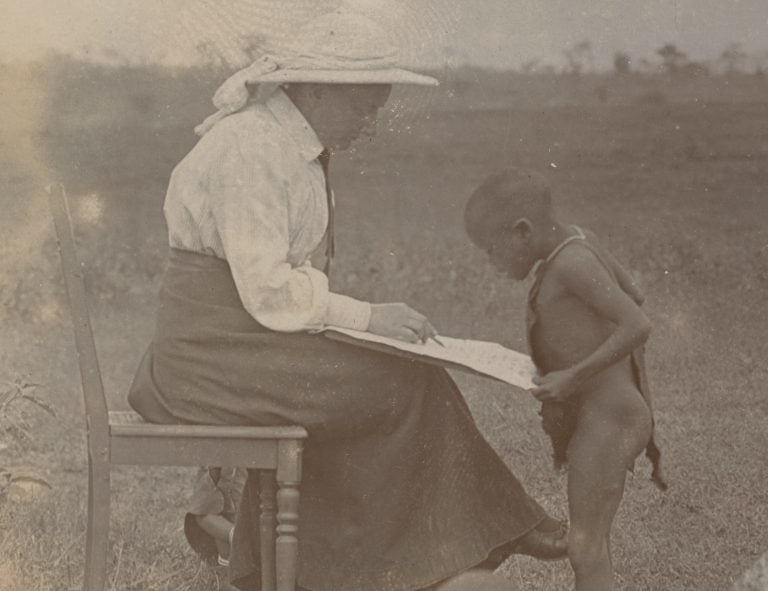

**Minnie Watson**

Smiling for the camera while wearing a safari-style hat and necktie, the Dundee-born teacher and missionary looked perfectly at ease as she posed for the camera alongside a group of children dressed in traditional Kenyan clothing.

The drought, famine and disease Minnie Watson endured in East Africa in the early 20th century was a world away from the poverty being experienced by many working people thousands of miles away in her hometown of Dundee.

Minnie Watson

But as the first female Presbyterian Missionary in Kenya, Mrs. Watson overcame these extreme hardships alongside the Kenyans to fulfil her mission of spreading the Gospel.

Today, it is another Presbyterian Missionary from Dundee – Mary Slessor – who often comes to mind when thinking of those who left a dramatic and lasting impact on generations of Africans.

But Minnie Watson was just as courageous and, almost 70 years after her death, the extraordinary legacy of the ship captain’s daughter lives on.

She helped lay the foundations of the Presbyterian Church of East Africa (PCEA) which today has around 3.5 million members and runs a network of schools, hospitals and universities.

Born in 1867, Minnie Watson followed her fiancé, the Rev Thomas Watson, who was also from Dundee to the former British colony in 1899 after he established the Scottish Mission in Thogoto, Kikuyu.

They soon married, but barely a year later, he died of pneumonia leaving the “devoted” 32-year-old to assume responsibility for the mission.

Education and welfare was Mrs. Watson’s primary focus and she established an extensive network of Mission Schools for girls and boys.

• Kenya’s first President Jomo Kenyatta, father of the current *President Uhuru Kenyatta, is a former pupil and was baptized in Watson-Scott Memorial Church.

• The Scottish Mission was originally funded by Christian directors of the Imperial East Africa Company but was taken over by the Church of Scotland 12 months after Mr Watson died.

• Mrs. Watson, who was head teacher at the Mission Schools system, was described by former pupils as an outstanding Christian role model – always loving, humble, patient but strict when necessary.

Smiling for the camera while wearing a safari-style hat and necktie, the Dundee-born teacher and missionary looked perfectly at ease as she posed for the camera alongside a group of children dressed in traditional Kenyan clothing.

The drought, famine and disease Minnie Watson endured in East Africa in the early 20th century was a world away from the poverty being experienced by many working people thousands of miles away in her hometown of Dundee.

Minnie Watson

But as the first female Presbyterian Missionary in Kenya, Mrs. Watson overcame these extreme hardships alongside the Kenyans to fulfil her mission of spreading the Gospel.

Today, it is another Presbyterian Missionary from Dundee – Mary Slessor – who often comes to mind when thinking of those who left a dramatic and lasting impact on generations of Africans.

But Minnie Watson was just as courageous and, almost 70 years after her death, the extraordinary legacy of the ship captain’s daughter lives on.

She helped lay the foundations of the Presbyterian Church of East Africa (PCEA) which today has around 3.5 million members and runs a network of schools, hospitals and universities.

Born in 1867, Minnie Watson followed her fiancé, the Rev Thomas Watson, who was also from Dundee to the former British colony in 1899 after he established the Scottish Mission in Thogoto, Kikuyu.

They soon married, but barely a year later, he died of pneumonia leaving the “devoted” 32-year-old to assume responsibility for the mission.

Education and welfare was Mrs. Watson’s primary focus and she established an extensive network of Mission Schools for girls and boys.

• Kenya’s first President Jomo Kenyatta, father of the current *President Uhuru Kenyatta, is a former pupil and was baptized in Watson-Scott Memorial Church.

• The Scottish Mission was originally funded by Christian directors of the Imperial East Africa Company but was taken over by the Church of Scotland 12 months after Mr Watson died.

• Mrs. Watson, who was head teacher at the Mission Schools system, was described by former pupils as an outstanding Christian role model – always loving, humble, patient but strict when necessary.

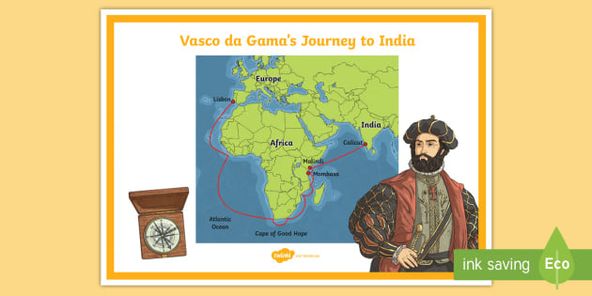

The Vasco da Gama pillar in Malindi, Kenya, symbolises many things to different people. The coastal people, the Mijikenda, consider it a symbol of a curse that has brought poverty and exploitation. To Christians, on the other hand, the pillar represents spiritual inspiration. Others see da Gama as a pioneer – the father of globalisation – and the pillar as a tourist attraction.

It has been 520 years since the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama landed in the harbour of Mombasa on 7 April 1498, on his way to India. The Arabs in Mombasa were not friendly to him, even attempting to sink his ship. The hostility prompted Gama to sail to the north. He arrived in Malindi on 14 April 1498.

The Sheikh of Malindi, whose name is not mentioned in the history books, was a rival to the Sheikh of Mombasa. He welcomed da Gama, giving him fresh water and food. Da Gama became close to the Sheikh. The relationship grew stronger, to the extent that the Sheikh gave da Gama a pilot sailor, Ibn Majid, to guide him to India, when he departed a few weeks later. On his return from India the following year – 1499 – da Gama built the pillar.

The pillar, known as Vasco da Gama’s Cross, or the Padrao, consists of a cross and the Portuguese coat of arms. It was first built next to the Malindi Sheikh’s Palace. However, Muslim residents felt that the cross on top of it represented Christian domination in a Muslim territory. They destroyed it.

But da Gama explained to the Sheikh that the pillar marked his successful discovery of the sea route to India. It also gives sailing directions – India is to the east, and Malindi to the west of the pillar. The Sheikh allowed da Gama to set up the pillar further away from his palace. Some years later, in 1512, it was rebuilt at the seafront. By this stage, the political realities had changed. The Portuguese had made Malindi their northern headquarters.

Today, the pillar is visible from far away in the high sea. It serves as a sailing control tower, even without any light on it. It is believed to be one of the oldest European monuments in Africa – older than the famous Portuguese monument Fort Jesus, built in Mombasa between 1593 and 1596 to protect the port from outside invaders.

“Gama’s pillar is one of the attractions of the global history in Kenya,” says tour guide Jacob Owino. “Local and foreign tourists, researchers, teachers and students from around the world, including Kenyans, visit the site every year.” Owino feels that the monument keeps Kenya on the world map as a tourist destination.

However, today the monument is facing threats from the rising sea level – a product of climate change. “The rock on which the pillar stands has huge cracks due to beating and erosion of the sea waves,” says Caesar Bita, the curator of the Malindi Museum. “The metal beams of the concrete basement have rusted and cracked too.” According to Bita, unless something is done, the pillar may soon collapse into the Indian Ocean.

* * *

The Mijikenda are believed to be the first people to have occupied coastal Kenya in the early centuries. They are Bantus who came originally from southern Somalia. Mijikenda is a Kiswahili word, meaning “nine homes”. The tribe comprises nine sub-tribes – the Giriama, Digo, Rabai, Chonyi, Jibana, Duruma, Kauma, Ribe and Kambe. The Giriama and Digo are the largest sub-tribes.

The Mijikenda – who occupy several counties along Kenya’s coast – have been marginalised for centuries. Today, the community is largely poor and landless. Many are illiterate, which makes it difficult to find work. “We are poor and have lived in mud huts with palm-thatch roofs for centuries, and yet the Europeans live in stone houses,” Hassan Juma, a resident of Malindi, lamented. “They are our masters, and we are the servants. They use our daughters as supplements of their leisure.”

Government statistics indicate that 58.4 per cent of the population in Kilifi County lives below the poverty line, surviving on less than $1.25 per day. Companies that operate in Kenya’s coastal areas tend to get most of their skilled staff from other parts of the country, while the majority of the Mijikenda are employed as unskilled labour.

“This pillar is a symbol of exploitation, it is a curse for us as we are not benefiting out of it. Our misery began within the coming of foreigners into our land,” says Chengo Chanzu, a Mijikenda elder. He argues that the pillar and all the historic attractions in Malindi are of no benefit to the Mijikenda people. “We are poor, marginalised and landless. All that is here belongs to the same Europeans who put up the pillar,” he says.

Most of the Mijikenda are squatters, living in plots of land owned by absentee Arab landlords. So how did the Mijikenda lose their ancestral land? Traditionally, African indigenous people owned land collectively, not as individuals. This practice of communal land ownership can still be seen in some parts of Kenya today, especially in pastoralist communities, such as the Maasai, Turkana, Samburu and Pokot.

Kenya’s history has been one of successive colonisations. A shift towards land tenure ownership was introduced in the 15th century, during the Portuguese occupation. The Omani Arabs kicked out the Portuguese in the 19th century. Oman’s Sultan Said Seyyid moved his headquarters from Muscat to Zanzibar in 1856, and he became the ruler of the East African coast. It was around this time that the Sultan granted freehold titles of land to Arabs, leaving out the indigenous African population. Vast swathes of land were bought up by the sultan, his associates and other wealthy Arabs. Their descendants still own the land, making them today’s absentee landlords.

After Kenya’s independence from British rule in 1963, influential politicians grabbed much of the prime land in the coastal areas of Mombasa, Kilifi, Kwale and Taita Taveta. Subsequent Kenyan governments never addressed the coastal land injustices. Poverty, illiteracy and landlessness continued for the Mijikenda people. About 80 per cent of Africans in the coast are technically squatters. All the land is still owned by Arabs, Europeans, Asians – or by politically well connected Kenyans, mostly from up-country.

* * *

Eventually, the land issue and long-term marginalisation of the Mijikenda turned political. Over the years, they lost hope of any meaningful change of land policy. This led to the formation of the Mombasa Republican Council (MRC) in 1999. The MRC was formed as a political organisation that intended to fight for the coastal region’s secession from Kenya. The movement embarked on the recruitment of young people to fight for coastal liberation. Their slogan was “Pwani si Kenya”, meaning “the coastal region is not part of Kenya”.

The MRC highlighted the fact that the coastal strip was still technically under the rule of the Sultan of Zanzibar. After Kenya’s independence in 1963, the prime minister Jomo Kenyatta leased the strip for 50 years from the sultan. The MRC argued that the lease was due to expire in 2013 and the strip should be returned to the coastal people. They turned violent in their struggle for independence, attacking non-coastal people and other targets with machetes and guns. The attackers, mostly young people, wore black robes adorned with a star and crescent moon. The oath that they took included witchcraft practices to protect them from police bullets.

The MRC’s activities caused great insecurity along the coast. Several hotels were closed, and thousands of workers lost jobs as tourism declined. Foreign embassies in Kenya issued advisory notices for their citizens to avoid visiting certain parts in the coast. The government began police operations arresting the MRC members, and in 2010 the organisation was declared a criminal gang. During the operations, numerous members were arrested and tortured. Some disappeared. Sensing danger from the security operations against it, the organisation changed its tactics – deciding to use legal means to fight the ban that declared it a criminal gang. Since then, the MRC’s profile has dropped, with no more violence or even public statements.

But talk of secession has not entirely disappeared. In the run-up to the 2017 general elections, two governors – Hassan Joho of Mombasa and Amason King of Kilifi – publicly declared that they would use diplomatic, legal and other means to ensure the coastal region secedes from Kenya. The election passed and the debate cooled down. There has been little talk about secession since.

* * *

Besides the Mijikenda, Malindi is a cosmopolitan town that is home to Africans, Europeans, Arabs and Asians. The Arabs, Italians and Indians control nearly every aspect of the economy in the town. The Italians, who make up about 80 per cent of the Europeans in Malindi, are believed to own over 50 hotels, cottages and villas, although no official statistics were available to confirm this. Malindi’s current mix reflects the comings and goings of its history.

As well as Vasco da Gama’s pillar, there is a Portuguese Chapel built before St Francis Xavier visited Malindi in 1542. Some historians believe it was built at the same time as the pillar, in 1499. In the chapel’s compound are 36 graves of sailors and other prominent Malindi pioneers, mostly Portuguese and British colonialists. The town’s two pillar tombs, which sit near the Arab Market, are another beautiful attraction. Built in the 15th century, the two pillars are decorated with Chinese porcelain. The Malindi District Officer’s house, completed in 1890, exemplifies British architecture of the era. The Imperial British East Africa Company built the house for the first Malindi District Officer, Bell-Smith.

“We preserved this global historical heritage for centuries, though living in extreme poverty,” says Mathew Karisa, a local businessman. “The Europeans come here to enjoy our resources in front of us, in exchange for nothing.”

Amongst these remnants of colonisation remain sacred places for the indigenous residents. The Kaya Shrines are sacred places in the forests for the Mijikenda. This is where they practise their rituals – prayers, sacrifices and burials. The Mijikenda believe that the spirits of their ancestors live in the shrines.

The issue of land along the coast is a political time bomb yet to explode. Unless a long-term solution is found, the Mijikenda will be tenants in their own land for ever.

It has been 520 years since the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama landed in the harbour of Mombasa on 7 April 1498, on his way to India. The Arabs in Mombasa were not friendly to him, even attempting to sink his ship. The hostility prompted Gama to sail to the north. He arrived in Malindi on 14 April 1498.

The Sheikh of Malindi, whose name is not mentioned in the history books, was a rival to the Sheikh of Mombasa. He welcomed da Gama, giving him fresh water and food. Da Gama became close to the Sheikh. The relationship grew stronger, to the extent that the Sheikh gave da Gama a pilot sailor, Ibn Majid, to guide him to India, when he departed a few weeks later. On his return from India the following year – 1499 – da Gama built the pillar.

The pillar, known as Vasco da Gama’s Cross, or the Padrao, consists of a cross and the Portuguese coat of arms. It was first built next to the Malindi Sheikh’s Palace. However, Muslim residents felt that the cross on top of it represented Christian domination in a Muslim territory. They destroyed it.

But da Gama explained to the Sheikh that the pillar marked his successful discovery of the sea route to India. It also gives sailing directions – India is to the east, and Malindi to the west of the pillar. The Sheikh allowed da Gama to set up the pillar further away from his palace. Some years later, in 1512, it was rebuilt at the seafront. By this stage, the political realities had changed. The Portuguese had made Malindi their northern headquarters.

Today, the pillar is visible from far away in the high sea. It serves as a sailing control tower, even without any light on it. It is believed to be one of the oldest European monuments in Africa – older than the famous Portuguese monument Fort Jesus, built in Mombasa between 1593 and 1596 to protect the port from outside invaders.

“Gama’s pillar is one of the attractions of the global history in Kenya,” says tour guide Jacob Owino. “Local and foreign tourists, researchers, teachers and students from around the world, including Kenyans, visit the site every year.” Owino feels that the monument keeps Kenya on the world map as a tourist destination.

However, today the monument is facing threats from the rising sea level – a product of climate change. “The rock on which the pillar stands has huge cracks due to beating and erosion of the sea waves,” says Caesar Bita, the curator of the Malindi Museum. “The metal beams of the concrete basement have rusted and cracked too.” According to Bita, unless something is done, the pillar may soon collapse into the Indian Ocean.

* * *

The Mijikenda are believed to be the first people to have occupied coastal Kenya in the early centuries. They are Bantus who came originally from southern Somalia. Mijikenda is a Kiswahili word, meaning “nine homes”. The tribe comprises nine sub-tribes – the Giriama, Digo, Rabai, Chonyi, Jibana, Duruma, Kauma, Ribe and Kambe. The Giriama and Digo are the largest sub-tribes.

The Mijikenda – who occupy several counties along Kenya’s coast – have been marginalised for centuries. Today, the community is largely poor and landless. Many are illiterate, which makes it difficult to find work. “We are poor and have lived in mud huts with palm-thatch roofs for centuries, and yet the Europeans live in stone houses,” Hassan Juma, a resident of Malindi, lamented. “They are our masters, and we are the servants. They use our daughters as supplements of their leisure.”

Government statistics indicate that 58.4 per cent of the population in Kilifi County lives below the poverty line, surviving on less than $1.25 per day. Companies that operate in Kenya’s coastal areas tend to get most of their skilled staff from other parts of the country, while the majority of the Mijikenda are employed as unskilled labour.

“This pillar is a symbol of exploitation, it is a curse for us as we are not benefiting out of it. Our misery began within the coming of foreigners into our land,” says Chengo Chanzu, a Mijikenda elder. He argues that the pillar and all the historic attractions in Malindi are of no benefit to the Mijikenda people. “We are poor, marginalised and landless. All that is here belongs to the same Europeans who put up the pillar,” he says.

Most of the Mijikenda are squatters, living in plots of land owned by absentee Arab landlords. So how did the Mijikenda lose their ancestral land? Traditionally, African indigenous people owned land collectively, not as individuals. This practice of communal land ownership can still be seen in some parts of Kenya today, especially in pastoralist communities, such as the Maasai, Turkana, Samburu and Pokot.

Kenya’s history has been one of successive colonisations. A shift towards land tenure ownership was introduced in the 15th century, during the Portuguese occupation. The Omani Arabs kicked out the Portuguese in the 19th century. Oman’s Sultan Said Seyyid moved his headquarters from Muscat to Zanzibar in 1856, and he became the ruler of the East African coast. It was around this time that the Sultan granted freehold titles of land to Arabs, leaving out the indigenous African population. Vast swathes of land were bought up by the sultan, his associates and other wealthy Arabs. Their descendants still own the land, making them today’s absentee landlords.

After Kenya’s independence from British rule in 1963, influential politicians grabbed much of the prime land in the coastal areas of Mombasa, Kilifi, Kwale and Taita Taveta. Subsequent Kenyan governments never addressed the coastal land injustices. Poverty, illiteracy and landlessness continued for the Mijikenda people. About 80 per cent of Africans in the coast are technically squatters. All the land is still owned by Arabs, Europeans, Asians – or by politically well connected Kenyans, mostly from up-country.

* * *

Eventually, the land issue and long-term marginalisation of the Mijikenda turned political. Over the years, they lost hope of any meaningful change of land policy. This led to the formation of the Mombasa Republican Council (MRC) in 1999. The MRC was formed as a political organisation that intended to fight for the coastal region’s secession from Kenya. The movement embarked on the recruitment of young people to fight for coastal liberation. Their slogan was “Pwani si Kenya”, meaning “the coastal region is not part of Kenya”.

The MRC highlighted the fact that the coastal strip was still technically under the rule of the Sultan of Zanzibar. After Kenya’s independence in 1963, the prime minister Jomo Kenyatta leased the strip for 50 years from the sultan. The MRC argued that the lease was due to expire in 2013 and the strip should be returned to the coastal people. They turned violent in their struggle for independence, attacking non-coastal people and other targets with machetes and guns. The attackers, mostly young people, wore black robes adorned with a star and crescent moon. The oath that they took included witchcraft practices to protect them from police bullets.

The MRC’s activities caused great insecurity along the coast. Several hotels were closed, and thousands of workers lost jobs as tourism declined. Foreign embassies in Kenya issued advisory notices for their citizens to avoid visiting certain parts in the coast. The government began police operations arresting the MRC members, and in 2010 the organisation was declared a criminal gang. During the operations, numerous members were arrested and tortured. Some disappeared. Sensing danger from the security operations against it, the organisation changed its tactics – deciding to use legal means to fight the ban that declared it a criminal gang. Since then, the MRC’s profile has dropped, with no more violence or even public statements.

But talk of secession has not entirely disappeared. In the run-up to the 2017 general elections, two governors – Hassan Joho of Mombasa and Amason King of Kilifi – publicly declared that they would use diplomatic, legal and other means to ensure the coastal region secedes from Kenya. The election passed and the debate cooled down. There has been little talk about secession since.

* * *

Besides the Mijikenda, Malindi is a cosmopolitan town that is home to Africans, Europeans, Arabs and Asians. The Arabs, Italians and Indians control nearly every aspect of the economy in the town. The Italians, who make up about 80 per cent of the Europeans in Malindi, are believed to own over 50 hotels, cottages and villas, although no official statistics were available to confirm this. Malindi’s current mix reflects the comings and goings of its history.

As well as Vasco da Gama’s pillar, there is a Portuguese Chapel built before St Francis Xavier visited Malindi in 1542. Some historians believe it was built at the same time as the pillar, in 1499. In the chapel’s compound are 36 graves of sailors and other prominent Malindi pioneers, mostly Portuguese and British colonialists. The town’s two pillar tombs, which sit near the Arab Market, are another beautiful attraction. Built in the 15th century, the two pillars are decorated with Chinese porcelain. The Malindi District Officer’s house, completed in 1890, exemplifies British architecture of the era. The Imperial British East Africa Company built the house for the first Malindi District Officer, Bell-Smith.

“We preserved this global historical heritage for centuries, though living in extreme poverty,” says Mathew Karisa, a local businessman. “The Europeans come here to enjoy our resources in front of us, in exchange for nothing.”

Amongst these remnants of colonisation remain sacred places for the indigenous residents. The Kaya Shrines are sacred places in the forests for the Mijikenda. This is where they practise their rituals – prayers, sacrifices and burials. The Mijikenda believe that the spirits of their ancestors live in the shrines.

The issue of land along the coast is a political time bomb yet to explode. Unless a long-term solution is found, the Mijikenda will be tenants in their own land for ever.

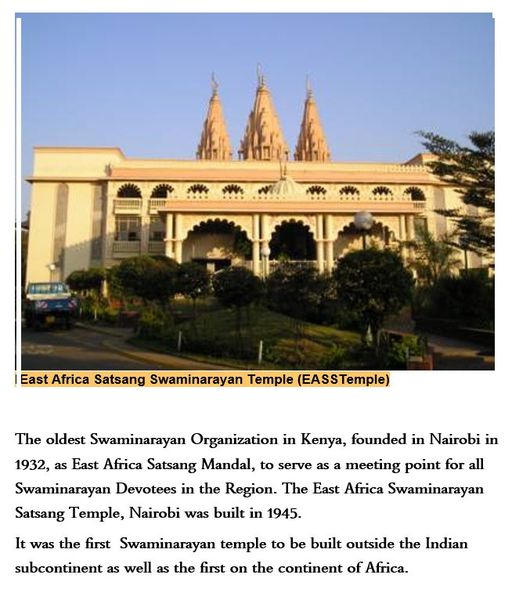

Hinduism in Kenya mainly comes from coastal trade routes between primarily between Gujarat, Marwar, Odisha and the Chola empire in India and East Africa.

The influence of Hinduism in Kenya began in early 1st millennium AD when there was trade between East Africa and Indian subcontinent. Archaeological evidence of small Hindu settlements have been found mainly in Zanzibar and coastal parts of Kenya, Swahili coast, Zimbabwe and Madagascar. Many words in Swahili language have their etymological roots in Indian languages associated with Hinduism.

The origin of the Kenyan Gujarati dates back to the late 1800s (early 1900s), when British colonialists brought laborers from India to build the Uganda–Kenya railway. Many of the laborers, rather than travel back to the Indian subcontinent, simply settled in Kenya, and slowly brought with them a host of hopefuls willing to start afresh.

Demographics

One percent of Kenyan population practiced Hinduism as reported by IRF. However, according to the 2019 Census, there were 60,287 Hindus in Kenya, who constitute 0.13% of the population.

The influence of Hinduism in Kenya began in early 1st millennium AD when there was trade between East Africa and Indian subcontinent. Archaeological evidence of small Hindu settlements have been found mainly in Zanzibar and coastal parts of Kenya, Swahili coast, Zimbabwe and Madagascar. Many words in Swahili language have their etymological roots in Indian languages associated with Hinduism.

The origin of the Kenyan Gujarati dates back to the late 1800s (early 1900s), when British colonialists brought laborers from India to build the Uganda–Kenya railway. Many of the laborers, rather than travel back to the Indian subcontinent, simply settled in Kenya, and slowly brought with them a host of hopefuls willing to start afresh.

Demographics

One percent of Kenyan population practiced Hinduism as reported by IRF. However, according to the 2019 Census, there were 60,287 Hindus in Kenya, who constitute 0.13% of the population.

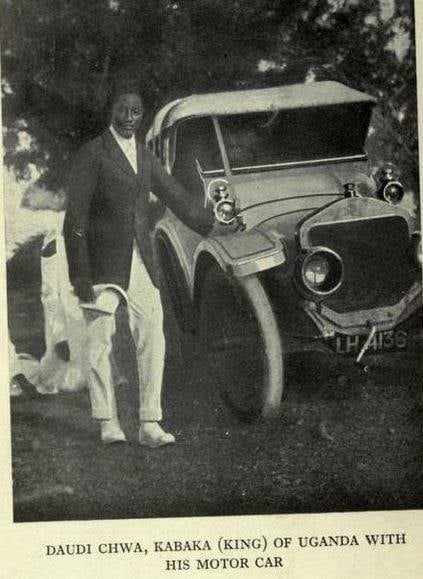

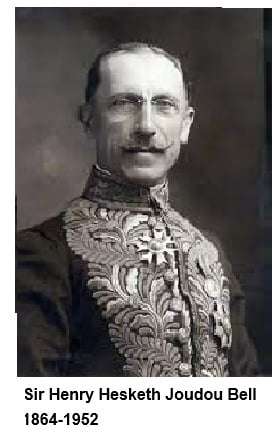

**Sir Henry Hesketh Joudou Bell**, the governor of Uganda Protectorate (1905 -1913) brought in a 1906 Albion 16HP engine car (manufactured by Albion Motors. This car arrived in Uganda on the 20th April 1908.

**Kabaka** **Daudi Chwa** **II** owned the first car in Buganda ,1910 Straker-Squire Mark 1 car. Kabaka Chwa born in 1896 became a King in 1897 when he was just one year old. While some accounts claim that Sir Hesketh Bell brought the car as a gift for Kabaka Chwa, the King was only 12 years at that time and governance of Buganda Kingdom,

***Achievements***

• Bell's many achievements in Uganda have been summarized as a teaching aid. One of the most important was a scheme for suppressing sleeping sickness, which Bell proposed in August 1907. After the Treasury authorized the funds for the work, the natives were moved from the fly-infested district on the shores of Lake Victoria to healthy locations inland. The sick were placed in segregation camps to undergo the so-called atoxyl treatment; an estimated 20,000 people were dealt with. The shores of Lake Victoria were cleared of all vegetation, thus removing the presence of the *tsetse fly*.

• Hesketh Bell’s vision for Uganda included major development of its railway. By 1909 to had battled hard for approval of two schemes: first, a line from Jinja, on the north shore of Lake Victoria to Kakindu and then to Lake Kioga; and, second, a direct line from Kampala to Lake Albert.

Extra notes

Port Bell is named after Henry Hesketh Bell, a British commissioner, who took over administration of Britain’s interests in Uganda in 1906. Its rail link is a branch line from the Kampala-Jinja main line.

Lake Victoria ferries operate from Port Bell linking Kampala to other rail head ports on Lake Victoria including Jinja, Kisumu, Musoma, and Mwanza. When the first stage of the Uganda Railway was completed in 1901, the rail head was at Kisumu, 12 hours journey from Port Bell by ship. Ferries brought goods by lake between Port Bell and Kisumu. It was not until 1931 that the main line of the railway from Nakuru reached Kampala and then Port Bell.

Bell Lager was the first Ugandan beer to be brewed in Uganda in 1950. It gets its name from the Port Bell pier where it is located along the shores of Lake Victoria. It is currently Uganda Breweries Limited's flagship beer and the number one premium lager in Uganda

@QuadroK4000 now you know how Bell Lager got its name

**Kabaka** **Daudi Chwa** **II** owned the first car in Buganda ,1910 Straker-Squire Mark 1 car. Kabaka Chwa born in 1896 became a King in 1897 when he was just one year old. While some accounts claim that Sir Hesketh Bell brought the car as a gift for Kabaka Chwa, the King was only 12 years at that time and governance of Buganda Kingdom,

***Achievements***

• Bell's many achievements in Uganda have been summarized as a teaching aid. One of the most important was a scheme for suppressing sleeping sickness, which Bell proposed in August 1907. After the Treasury authorized the funds for the work, the natives were moved from the fly-infested district on the shores of Lake Victoria to healthy locations inland. The sick were placed in segregation camps to undergo the so-called atoxyl treatment; an estimated 20,000 people were dealt with. The shores of Lake Victoria were cleared of all vegetation, thus removing the presence of the *tsetse fly*.

• Hesketh Bell’s vision for Uganda included major development of its railway. By 1909 to had battled hard for approval of two schemes: first, a line from Jinja, on the north shore of Lake Victoria to Kakindu and then to Lake Kioga; and, second, a direct line from Kampala to Lake Albert.

Extra notes

Port Bell is named after Henry Hesketh Bell, a British commissioner, who took over administration of Britain’s interests in Uganda in 1906. Its rail link is a branch line from the Kampala-Jinja main line.

Lake Victoria ferries operate from Port Bell linking Kampala to other rail head ports on Lake Victoria including Jinja, Kisumu, Musoma, and Mwanza. When the first stage of the Uganda Railway was completed in 1901, the rail head was at Kisumu, 12 hours journey from Port Bell by ship. Ferries brought goods by lake between Port Bell and Kisumu. It was not until 1931 that the main line of the railway from Nakuru reached Kampala and then Port Bell.

Bell Lager was the first Ugandan beer to be brewed in Uganda in 1950. It gets its name from the Port Bell pier where it is located along the shores of Lake Victoria. It is currently Uganda Breweries Limited's flagship beer and the number one premium lager in Uganda

@QuadroK4000 now you know how Bell Lager got its name

Year_1903_The_first_motor_car in Kenya was a De Dion Bouton which was lowered from a steamship in December 1903 in Mombasa, into the hands of its proud owner George Wilson, an Australian road engineer. At the time, the De Dion Bouton was the best selling motor car worldwide, producing 400 cars and 3,200 engines in 1900. Built in France, the car was propelled by an 8cv single cylinder four stroke petrol engine.

Received with much applause in Mombasa, there were just a few niggling problems. The car could not be started for two days as there was no petrol or petrol stations to supply the combustible fluid. Its petrol had to be offloaded from the ship, in four- gallon tins, similar to the kerosene debes that were the vogue at the time.

In the meantime, Wilson, ably assisted by his wife, had to study an instructions manual to discover where to put the oil and grease and how to adjust the various brass levers on the steering wheel to get the spark and fuel mixture just right.

It soon became evident that Kenya had only one major road or, more accurately, a glorified ox-cart track between Mombasa and Mumia (today’s Mumias). There were no garages and the car was notoriously unreliable, breaking down with unparalleled frequency.

There is something about men and machines, especially of the chariot variety — an insatiable desire to go faster and farther than the chap next door. The greater the challenge, the more man is driven to outdo his adversary.

Kenya, with its hostile terrain and lack of infrastructure provided just the right challenge and it was in this environment that the motor industry developed. More earth roads were built chiefly between administrative centers notably, Nairobi-Fort Hall (Murang’a), Lumbwa-Kericho, Voi-Taveta and Machakos-Athi River.

To demonstrate the road’s attraction to early motorists is the fact that it took another 23 years, after the arrival of the first car, before a petrol vehicle completed the journey from Mombasa to Nairobi.

This achievement is credited to the one-armed John Douglas and Syd Downey on a Harley Davidson motorcycle in 1926 speeded up by the presence of lions enroute, and later the same year Galton-Fenzi matched them in a Riley car. There were many cars in Nairobi before then but they had all been transported by rail from Mombasa.Fuelled by the popularity of the legendary Ford Model T (Tin Lizzie), the vehicle population in Kenya had reached 1,000 by 1919. Up to this time there was no requirement for a driving test, no highway code, no road tax and no insurance.

Seeing the need for order in the burgeoning motor industry, Lionel Douglas Galton-Fenzi (1881-1937), an automobile enthusiast and adventurer, helped to found the East African Automobile Association — forerunner of today’s Automobile Association of Kenya — in September 1919.

He was the prime mover of motoring in Kenya opening up countless road routes across the length and breadth of the country. He helped bring sanity to motoring on our roads and in motorsports.

In 1923, he began negotiating for loan cars which he could test under East African conditions. He received several cars under this arrangement amongst which was a Riley 12/50 with which he pioneered the Nairobi-Mombasa route.

Erected at the junction of Kenyatta Avenue and Koinange Street is the Galton-Fenzi Memorial —also referred to as the Nairobi Military Stone.

The memorial was erected in honour of Lionel Douglas Galton-Fenzi for his pioneering achievements for the motoring industry in Kenya.

Fuelled by the popularity of the legendary Ford Model T (Tin Lizzie), the vehicle population in Kenya had reached 1,000 by 1919. Up to this time there was no requirement for a driving test, no highway code, no road tax and no insurance.

Seeing the need for order in the burgeoning motor industry, Lionel Douglas Galton-Fenzi (1881-1937), an automobile enthusiast and adventurer, helped to found the East African Automobile Association — forerunner of today’s Automobile Association of Kenya — in September 1919.

He was the prime mover of motoring in Kenya opening up countless road routes across the length and breadth of the country. He helped bring sanity to motoring on our roads and in motorsports.

Received with much applause in Mombasa, there were just a few niggling problems. The car could not be started for two days as there was no petrol or petrol stations to supply the combustible fluid. Its petrol had to be offloaded from the ship, in four- gallon tins, similar to the kerosene debes that were the vogue at the time.

In the meantime, Wilson, ably assisted by his wife, had to study an instructions manual to discover where to put the oil and grease and how to adjust the various brass levers on the steering wheel to get the spark and fuel mixture just right.

It soon became evident that Kenya had only one major road or, more accurately, a glorified ox-cart track between Mombasa and Mumia (today’s Mumias). There were no garages and the car was notoriously unreliable, breaking down with unparalleled frequency.

There is something about men and machines, especially of the chariot variety — an insatiable desire to go faster and farther than the chap next door. The greater the challenge, the more man is driven to outdo his adversary.

Kenya, with its hostile terrain and lack of infrastructure provided just the right challenge and it was in this environment that the motor industry developed. More earth roads were built chiefly between administrative centers notably, Nairobi-Fort Hall (Murang’a), Lumbwa-Kericho, Voi-Taveta and Machakos-Athi River.

To demonstrate the road’s attraction to early motorists is the fact that it took another 23 years, after the arrival of the first car, before a petrol vehicle completed the journey from Mombasa to Nairobi.

This achievement is credited to the one-armed John Douglas and Syd Downey on a Harley Davidson motorcycle in 1926 speeded up by the presence of lions enroute, and later the same year Galton-Fenzi matched them in a Riley car. There were many cars in Nairobi before then but they had all been transported by rail from Mombasa.Fuelled by the popularity of the legendary Ford Model T (Tin Lizzie), the vehicle population in Kenya had reached 1,000 by 1919. Up to this time there was no requirement for a driving test, no highway code, no road tax and no insurance.

Seeing the need for order in the burgeoning motor industry, Lionel Douglas Galton-Fenzi (1881-1937), an automobile enthusiast and adventurer, helped to found the East African Automobile Association — forerunner of today’s Automobile Association of Kenya — in September 1919.

He was the prime mover of motoring in Kenya opening up countless road routes across the length and breadth of the country. He helped bring sanity to motoring on our roads and in motorsports.

In 1923, he began negotiating for loan cars which he could test under East African conditions. He received several cars under this arrangement amongst which was a Riley 12/50 with which he pioneered the Nairobi-Mombasa route.

Erected at the junction of Kenyatta Avenue and Koinange Street is the Galton-Fenzi Memorial —also referred to as the Nairobi Military Stone.

The memorial was erected in honour of Lionel Douglas Galton-Fenzi for his pioneering achievements for the motoring industry in Kenya.

Fuelled by the popularity of the legendary Ford Model T (Tin Lizzie), the vehicle population in Kenya had reached 1,000 by 1919. Up to this time there was no requirement for a driving test, no highway code, no road tax and no insurance.

Seeing the need for order in the burgeoning motor industry, Lionel Douglas Galton-Fenzi (1881-1937), an automobile enthusiast and adventurer, helped to found the East African Automobile Association — forerunner of today’s Automobile Association of Kenya — in September 1919.

He was the prime mover of motoring in Kenya opening up countless road routes across the length and breadth of the country. He helped bring sanity to motoring on our roads and in motorsports.

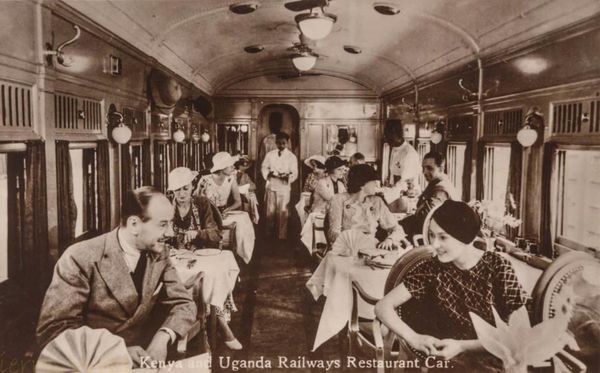

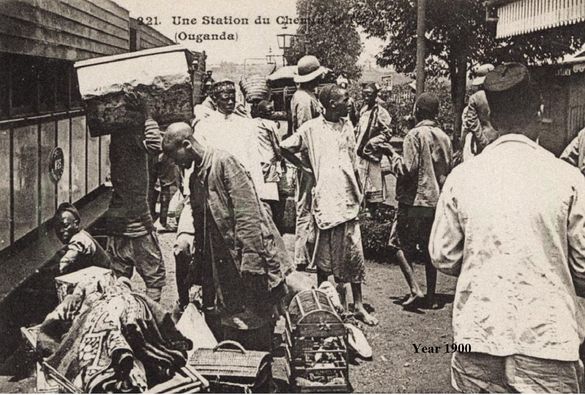

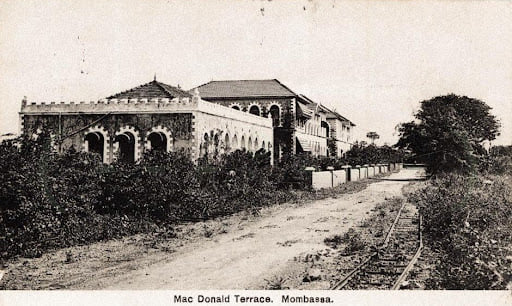

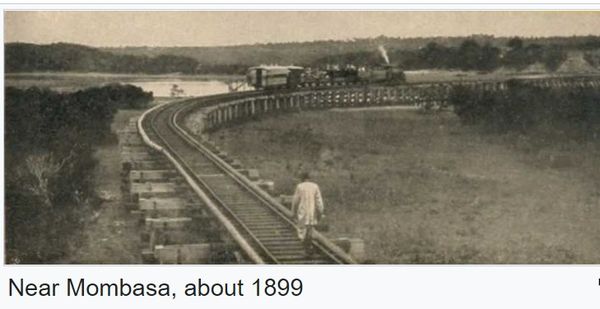

Year_1895_Uganda_Railway 1895 (1929 became Kenya Uganda Railway).

Before the railway's construction, the British East Africa Company had begun the Mackinnon-Sclater road, 600 mile ox-cart track from Mombasa to Busia in Kenya, in 1890.

In July 1890, Britain was party to a series of anti-slavery measures agreed at the Brussels Conference Act of 1890. In December 1890, a letter from the Foreign Office to the treasury proposed constructing a railway from Mombasa to Uganda to disrupt the traffic of slaves from its source in the interior to the coast.

With steam-powered access to Uganda, the British could transport people and soldiers to ensure dominance of the African Great Lakes region.

In December 1891 Captain James Macdonald began an extensive survey which lasted until November 1892. At the time there was only one caravan route across the length of the country, forcing Macdonald and his party to march 4,280 miles across unknown routes with limited supplies of water or food. The survey led to the first general map of the region.

The Uganda Railway was named after its ultimate destination, for its entire original 660 mile length actually lay in what would become Kenya. Construction began at the port city of Mombasa in British East Africa in 1896 and finished at the line's terminus, Kisumu, on the eastern shore of Lake Victoria, in 1901.

The railway was a huge logistical achievement and became strategically and economically vital for both Uganda and Kenya. It helped to suppress slavery, by removing the need for humans in the transport of goods.

In August 1895, a bill was introduced at Westminster, becoming the Uganda Railway Act 1896 which authorized the construction of a railway from Mombasa to the shores of Lake Victoria.

Nearly all the workers involved on the construction of the line came from British India. An agent was appointed in Karachi responsible for recruiting coolies, artisans and subordinate officers and a branch office was located in Lahore, the principal recruiting center. Workers were sourced from villages in the Punjab and sent to Karachi on specially chartered steamers belonging to the British India Steam Navigation Company. Shortly after recruitment began, a plague broke out in India, seriously delaying the advancement of the railway. The Government of India only permitted recruitment and emigration to resume on the creation of a quarantine camp at Budapore, financed by the Uganda Railway, and where recruits were required to spend fourteen days in quarantine before departure.

A total of 35,729 coolies and artisans were recruited along with 1,082 subordinate officers, totaling 36,811 persons. Each coolie signed a contract for three years at twelve rupees per month with free rations and return passage to their place of enlistment. They received half-pay when in hospital and free medical attendance. Recruitment continued between December 1895 and March 1901, and the first coolies began to return to India after their contracts ended in 1899. 2,493 workers died during the construction of the railway between 1895 and 1903 at a rate of 357 annually. While most of the surviving Indians returned home, 6,724 decided to remain after the line's completion, creating a community of Indians in East Africa.

Former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt (seated, at left) and friends mount the observation platform of a Uganda Railway locomotive

Tsavo man-eating lions

The incidents for which the building of the railway may be most noted are the killings of a number of construction workers in 1898, during the building of a bridge across the Tsavo River. In 1898, two lions terrorized crews constructing a railroad bridge over the Tsavo River, killing—according to some estimates—135 people were killed.

the cost has been estimated by one source at £3 million in 1894 money, which is or £650 million in 2016 money by another source.

Because of the Through everything—through the forests, through the ravines, through troops of marauding lions, through famine, through war, through five years of excoriating Parliamentary debate, muddled and marched the railway."

Branch lines were built to Thika in 1913, Lake Magadi in 1915, Kitale in 1926, Naro Moro in 1927 and from Tororo to Soroti in 1929. In 1929 the Uganda Railway became Kenya and Uganda Railways and Harbors (KURH), which in 1931 completed a branch line to Mount Kenya and extended the main line from Nakuru to Kampala in Uganda. In 1948 KURH became part of the East African Railways Corporation, which added the line from Kampala to Kasese in western Uganda in 1956 and extended to it to Arua near the border with Zaïre in 1964.

Inland shipping - Lake Victoria ferries and steamers

Almost from its inception the Uganda Railway developed shipping services on Lake Victoria. In 1898 it launched the 110 ton SS William Mackinnon at Kisumu, having assembled the vessel from a "knock down" kit supplied by Bow, McLachlan and Company of Paisley in Scotland. A succession of further Bow, McLachlan & Co. "knock down" kits followed. The 662 ton sister ships SS Winifred and SS Sybil (1902 and 1903), the 1,134 ton SS Clement Hill (1907) and the 1,300 ton sister ships SS Rusinga and SS Usoga (1914 and 1915) were combined passenger and cargo ferries. The 812 ton SS Nyanza (launched after Clement Hill) was purely a cargo ship. The 228 ton SS Kavirondo launched in 1913 was a tugboat. Two more tugboats from Bow, McLachlan were added in1925: SS Buganda and SS Buvuma.

The rail journey stirred many a romantic passage, like this one from former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, who rode the line to start his world-famous safari

Before the railway's construction, the British East Africa Company had begun the Mackinnon-Sclater road, 600 mile ox-cart track from Mombasa to Busia in Kenya, in 1890.

In July 1890, Britain was party to a series of anti-slavery measures agreed at the Brussels Conference Act of 1890. In December 1890, a letter from the Foreign Office to the treasury proposed constructing a railway from Mombasa to Uganda to disrupt the traffic of slaves from its source in the interior to the coast.

With steam-powered access to Uganda, the British could transport people and soldiers to ensure dominance of the African Great Lakes region.

In December 1891 Captain James Macdonald began an extensive survey which lasted until November 1892. At the time there was only one caravan route across the length of the country, forcing Macdonald and his party to march 4,280 miles across unknown routes with limited supplies of water or food. The survey led to the first general map of the region.

The Uganda Railway was named after its ultimate destination, for its entire original 660 mile length actually lay in what would become Kenya. Construction began at the port city of Mombasa in British East Africa in 1896 and finished at the line's terminus, Kisumu, on the eastern shore of Lake Victoria, in 1901.

The railway was a huge logistical achievement and became strategically and economically vital for both Uganda and Kenya. It helped to suppress slavery, by removing the need for humans in the transport of goods.

In August 1895, a bill was introduced at Westminster, becoming the Uganda Railway Act 1896 which authorized the construction of a railway from Mombasa to the shores of Lake Victoria.

Nearly all the workers involved on the construction of the line came from British India. An agent was appointed in Karachi responsible for recruiting coolies, artisans and subordinate officers and a branch office was located in Lahore, the principal recruiting center. Workers were sourced from villages in the Punjab and sent to Karachi on specially chartered steamers belonging to the British India Steam Navigation Company. Shortly after recruitment began, a plague broke out in India, seriously delaying the advancement of the railway. The Government of India only permitted recruitment and emigration to resume on the creation of a quarantine camp at Budapore, financed by the Uganda Railway, and where recruits were required to spend fourteen days in quarantine before departure.

A total of 35,729 coolies and artisans were recruited along with 1,082 subordinate officers, totaling 36,811 persons. Each coolie signed a contract for three years at twelve rupees per month with free rations and return passage to their place of enlistment. They received half-pay when in hospital and free medical attendance. Recruitment continued between December 1895 and March 1901, and the first coolies began to return to India after their contracts ended in 1899. 2,493 workers died during the construction of the railway between 1895 and 1903 at a rate of 357 annually. While most of the surviving Indians returned home, 6,724 decided to remain after the line's completion, creating a community of Indians in East Africa.

Former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt (seated, at left) and friends mount the observation platform of a Uganda Railway locomotive

Tsavo man-eating lions

The incidents for which the building of the railway may be most noted are the killings of a number of construction workers in 1898, during the building of a bridge across the Tsavo River. In 1898, two lions terrorized crews constructing a railroad bridge over the Tsavo River, killing—according to some estimates—135 people were killed.

the cost has been estimated by one source at £3 million in 1894 money, which is or £650 million in 2016 money by another source.

Because of the Through everything—through the forests, through the ravines, through troops of marauding lions, through famine, through war, through five years of excoriating Parliamentary debate, muddled and marched the railway."

Branch lines were built to Thika in 1913, Lake Magadi in 1915, Kitale in 1926, Naro Moro in 1927 and from Tororo to Soroti in 1929. In 1929 the Uganda Railway became Kenya and Uganda Railways and Harbors (KURH), which in 1931 completed a branch line to Mount Kenya and extended the main line from Nakuru to Kampala in Uganda. In 1948 KURH became part of the East African Railways Corporation, which added the line from Kampala to Kasese in western Uganda in 1956 and extended to it to Arua near the border with Zaïre in 1964.

Inland shipping - Lake Victoria ferries and steamers

Almost from its inception the Uganda Railway developed shipping services on Lake Victoria. In 1898 it launched the 110 ton SS William Mackinnon at Kisumu, having assembled the vessel from a "knock down" kit supplied by Bow, McLachlan and Company of Paisley in Scotland. A succession of further Bow, McLachlan & Co. "knock down" kits followed. The 662 ton sister ships SS Winifred and SS Sybil (1902 and 1903), the 1,134 ton SS Clement Hill (1907) and the 1,300 ton sister ships SS Rusinga and SS Usoga (1914 and 1915) were combined passenger and cargo ferries. The 812 ton SS Nyanza (launched after Clement Hill) was purely a cargo ship. The 228 ton SS Kavirondo launched in 1913 was a tugboat. Two more tugboats from Bow, McLachlan were added in1925: SS Buganda and SS Buvuma.

The rail journey stirred many a romantic passage, like this one from former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, who rode the line to start his world-famous safari

In 1993, a Frenchman named Emile Leray driving a Citroen car in a remote area of the Moroccan desert had a breakdown and became stranded. To survive, he tore down the car, built a motorcycle from the parts and then rode it back to civilization.

Unfortunately he was arrested by Moroccan authorities coz he didn't have a motorcycle license instead had an initial vehicle license

Unfortunately he was arrested by Moroccan authorities coz he didn't have a motorcycle license instead had an initial vehicle license

Aviator

Elder Lister

Well done. This is gold.

Lakini hapa inakaa chumbi imezidi

Lakini hapa inakaa chumbi imezidi

In 1993, a Frenchman named Emile Leray driving a Citroen car in a remote area of the Moroccan desert had a breakdown and became stranded. To survive, he tore down the car, built a motorcycle from the parts and then rode it back to civilization.

It's Me Scumbag

Elder Lister

sio uwongo, google it and confirmWell done. This is gold.

Lakini hapa inakaa chumbi imezidi

MacKinnon = Mzungu@Meria what is the difference between MacKinnon and Tippu Tip?

Tippu Tip = Afro Arab, muarabu mweusi

nikii we?

ask that question unakanyagia!