Mwalimu-G

Elder Lister

Under the skin

There’s a good chance that you’ll be at the sharp end of a hypodermic needle over the next few months – at least, I hope you will. The various Covid-19 vaccines are finally reaching the people who need them most: 1,296,432 doses had been administered in the UK by the first week of January. Assuming the entire population receives both doses – sadly unlikely, for one reason or another – that’s something like 130 million disposable needles that will be used in the UK alone.

The humble hypodermic has countless uses in contemporary medicine, an essential piece of kit everywhere from Addis Ababa to Zagreb. But who was the first to use it? As with most inventions, the history of hypodermic drug administration is a tangled one – no one person can claim to have been the inventor of the hypodermic syringe. Ancient physicians used various techniques to introduce drugs through punctures through the skin – following the example of venomous snakes and biting insects, as the physician and historian of medicine Norman Howard-Jones pointed out in 1947. But it was not until the mid-nineteenth century that specialised instruments for hypodermic drug administration were designed and employed.

This case report, published in the Dublin Medical Press in 1845, is regarded by many historians as the first description of a drug being administered hypodermically. The physician responsible was Francis Rynd, who worked at the Meath Hospital in Dublin – during an era when the Irish capital was one of the great European centres of hospital medicine.

Margaret Cox, aged 59, of spare habit, was admitted into hospital, May 18, 1844…

‘Of spare habit’ means simply that she was thin.

…complaining of acute pain over the entire left side of face, particularly in the left supra-orbital region, shooting into the eye, along the branches of the portio dura in the cheek, along the gums of both upper and lower jaw, much increased in this situation by shutting the mouth and pressing her teeth close together, and occasionally darting to the opposite side of the face and to the top and back of her head.

The supra-orbital region is the area around the eyebrow. ‘Portio dura’ is an antiquated term for the facial nerve, a significant structure with a wide range of important functions, from taste sensation to motor control of the facial muscles.

Most modern experts seem to believe that the woman was suffering from trigeminal neuralgia, an excruciatingly painful condition in which the facial nerve starts to ‘misfire’, sending inappropriate pain signals to the brain. The condition can be chronic and is difficult to treat.

She states that about six years ago she fell from a wall, and, in the act of falling, a stone struck her in the temple; that twelve months after this she was much exposed to cold, and one night was suddenly seized with the most agonizing pain in the situations above described.

It is not clear whether the injury or the cold had anything to do with the onset of the condition, though trigeminal neuralgia is sometimes caused by physical damage to the nerve.

She “thought her eye was being torn out of her head,” and her cheek from her face; it lasted about two hours, and then suddenly disappeared on taking a mouthful of ice. She had not had any return for three months, when it came back even worse than before, quite suddenly, one night on going out of a warm room into the cold air.

Trigeminal neuralgia often comes in almost unbearable waves, so this description certainly fits.

On this attack she was seized with chilliness, shivering, and slight nausea; the left eye lachrymated profusely, and became red with pain…

‘Lachrymated’ = wept.

…it went in darts through her whole head, face, and mouth, and the paroxysm lasted for three weeks, during which time she never slept. She was bled and blistered, and took opium for it, but without relief. It continued coming at irregular intervals, but each time generally more intense in character, until at last, weary of her existence, she came to Dublin for relief.

One of the idiosyncrasies of trigeminal neuralgia is that conventional painkillers are largely ineffective against it. Today the frontline treatments are anticonvulsants such as carbamazepine, but no such pharmaceutical wonders were available in 1844.

She had been salivated three times…

Meaning that she had been treated with mercury. At this date it was most often used as a syphilis drug; when administered in sufficient quantities it causes excessive salivation.

…and had been so much in the habit of taking laudanum that latterly half a drachm, three times in the day, had no effect in lulling the pain, and was the quantity she commonly took. She was a miserable sallow-complexioned looking creature, had been sleepless for months, and her face was furrowed with constant pain.

Understandably. Trigeminal neuralgia has been described as the ‘worst pain it is possible to imagine.’

On the 3rd of June a solution of fifteen grains of acetate of morphia, dissolved in one drachm of creosote, was introduced to the supra-orbital nerve, and along the course of the temporal, malar, and buccal nerves, by four punctures of an instrument made for the purpose.

Morphine acetate is a highly soluble salt of morphine, for a period in the nineteenth century the form in which the drug was most often used. It was investigated a few decades ago as an alternative to the more commonly used (and much less soluble) morphine sulphate, but for various reasons was deemed less satisfactory.

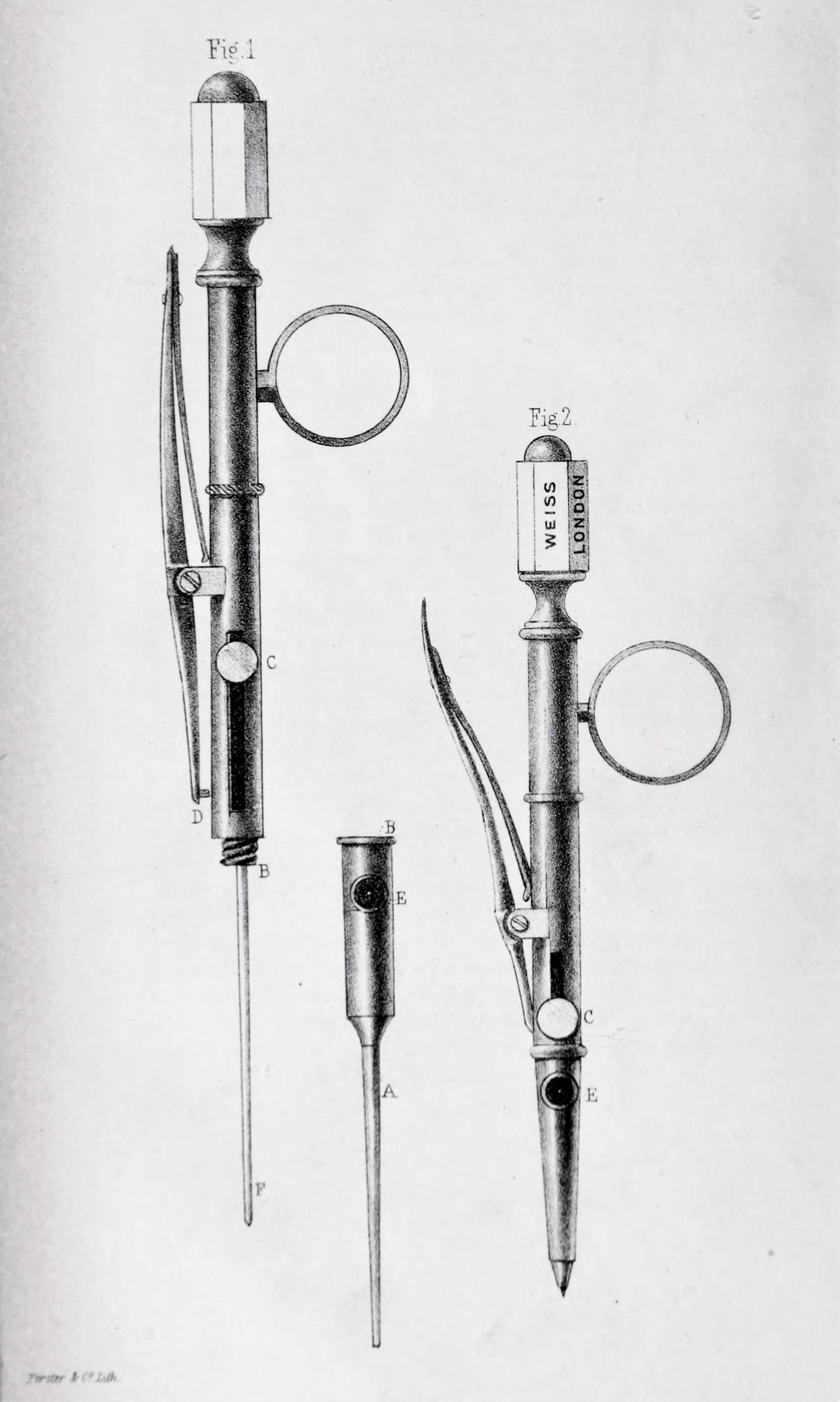

The most interesting thing about this section of the report, however, is the ‘instrument made for the purpose’ of injecting the drug. Dr Rynd did not include a description or illustration of this instrument – probably a mistake, as it was his opportunity to publicise his invention. We do know what it looked like, however, from an article he subsequently published in 1861:

Illustration of Francis Rynd’s trochar, used to inject morphine subcutaneously in 1844

Illustration of Francis Rynd’s trochar, used to inject morphine subcutaneously in 1844This is not a hypodermic syringe but a novel type of trochar: an instrument with a sharp tip and a cannula through which fluids can be introduced (or evacuated). It had a sharp needle to puncture the skin, but no plunger to propel fluids into the body; instead, the drug was dropped into the cannula, using ‘an ordinary writing-pen’, and then left to infiltrate the tissues by gravity alone.

In the space of a minute all pain (except that caused by the operation, which was very slight), had ceased, and she slept better that night than she had done for months. After the interval of a week she had slight return of pain in the gums of both upper and under jaw. The fluid was again introduced by two punctures made in the gum of each jaw, and the pain disappeared. After this the pain did not recur, and she was detained in hospital for some weeks, during which time her health improved, her sleep was restored, and she became quite a happy looking person. She left the hospital on the 1st of August in high spirits, and promised to return if she ever felt the slightest pain again. We conclude she continues well, for we have not heard from her since.

The treatment appears to have been successful, but the report raises some interesting questions. Morphine does not have any significant effect as a local anaesthetic, so is more likely to have worked as a systemic analgesic. But most textbooks will tell you that it is also ineffective against trigeminal neuralgia, which is notoriously intractable to painkilling drugs.

So what was going on? Either the patient was suffering from some other chronic pain condition against which morphine was effective, or – and I’m hypothesising wildly here – is it possible that a combination of morphine and the creosote in which it was dissolved (toxic, by the way) resulted in a nerve block? If you have any ideas, please do leave a comment below.

There’s an important postscript to this story. Many historians would agree that Francis Rynd was the first modern doctor to employ a specialised device to administer liquid drugs hypodermically. But the first description of a syringe used for the same purpose was a paper published in 1855 by the Edinburgh physician Alexander Wood. Two years earlier he had treated a patient with cervicobrachial neuralgia, pain of the arm and neck caused by inflammation of the brachial plexus. He also chose to inject the region of the nerve with morphine, but this time he used what he described as

one of the elegant little syringes, constructed…by Mr Ferguson of Giltspur Street, London.

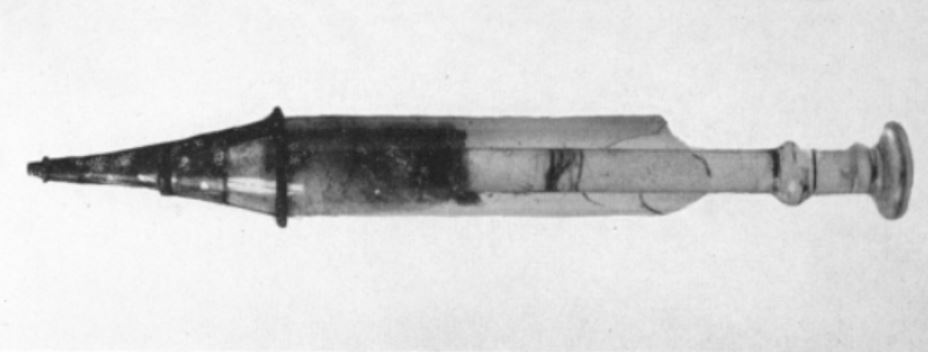

Syringes have been known in medicine for centuries, but until the mid-19th century they were large items, used typically for administering enemas. The ‘elegant little syringe’ manufactured by Mr Ferguson of Giltspur Street was intended for squirting acid on moles, a dubious method of removing them. Sadly we do not know what sort of needle Dr Wood attached to this item, but the cylinder and plunger of one of his syringes has survived. Billions of disposable hypodermics will be used in the coming months, pricking the skin of your arms as well as mine; but the little beauty below was possibly the very first.